A Nineteenth Century Medical Education

Medical training in the nineteenth century was very different to today; aspiring doctors were not taught at one university but could attend classes at a variety of universities and private schools, before sitting their final exams at a university medical school of their choice. The archive collection of Dominic Corrigan, who trained as a doctor in the 1820s, gives a valuable insight into medical training at the time, as he preserved the admittance tickets and certificates from the various courses he attended during his medical training (DC/2/1).

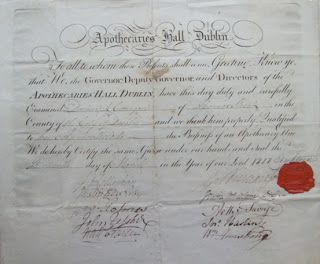

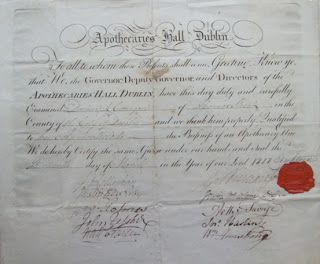

Corrigan started his education at the Lay College at Maynooth, and it was there that he seems to have settled on a career in medicine. He was apprenticed to Dr Edward Talbot O’Kelly, physician and apothecary to Maynooth College. In 1818 he was awarded a certificate of apprenticeship by Apothecaries Hall. When Corrigan left Maynooth he had both a good general education, as well as a basic knowledge of medical practice, a decided advantage over many of his contemporaries.[1]

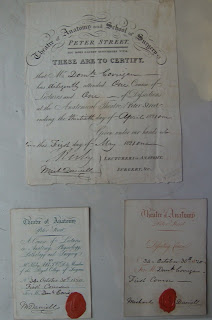

Corrigan spent five years from 1820 to 1825 studying medicine in Dublin and Edinburgh. From his surviving archive we can see that he took courses in Chemistry, Dissection, Anatomy, Physiology, Surgery, the Practice of Medicine, Pathology, Materia Medica, Pharmacy, Morbid Anatomy, the Institutes of Medicine, Clinical Lectures and finally Botany. In taking these courses Corrigan attended the University of Dublin and the School of Physic, Trinity College Dublin, as well as private medical schools; the Peter Street School, the Medical School in Ireland, Apothecaries Hall and Sir Patrick Dun’s Hospital, where he also spent a year on the wards. The collection also gives us the names of Corrigan’s teachers including the anatomists John Timothy Kirby and James Macartney, and John Crampton, professor of Materia Medica at the School of Physic, Trinity College.

Having attended five years of lectures in Dublin, Corrigan travelled to Edinburgh where he attended one series of lectures, in Botany, and wrote his thesis on Scrofula, or the King’s Evil. Corrigan took his medical finals and graduated in August 1825, with another eminent Irish physician and future College President, William Stokes (see left). Among the Corrigan papers are Corrigan’s final exam papers from Edinburgh, written in Latin (DC/2/1/9). The choice of Edinburgh for Irish medical students was not uncommon, of the 139 graduating students in Corrigan’s class, 44 were Irish.[2] Corrigan’s choice of Edinburgh seems to have been prompted by his former mentor Dr O’Kelly. Many years later in a letter full of reminiscences O’Kelly expresses his pride in Corrigan’s career and fondly remembers 'I was most anxious to persuade my old friend - your good father to send you to Edinburgh’.[3]

Corrigan’s medical education did not end in Edinburgh. In 1833-7 while working at the Charitable Infirmary, Jervis Street, he attended several series of lectures there on surgery and on the practice of surgery and in 1843 sat his membership exams for the Royal College of Surgeons in London. He was awarded an honorary doctorate of medicine by Trinity College Dublin in 1849 (DC/2/2/1). Due to a dispute with many prominent members of the medical profession over the Central Board of Health, established in 1846, Corrigan’s bid for membership of the King and Queen’s College of Physicians was blocked. Nine years later Corrigan turned up with many of his own medical students to sit the College’s licentiate exam; once he had gained entry in the College he rose quickly to become a member (1856) and president (1859), the first Catholic to hold this office.

Towards the end of his life Corrigan wrote an anonymous article ‘Reminiscences of the Dissecting Room’, published in the British Medical Journal, in which he recorded his student days and especially the then common occurrence of grave robbing, at that time the only way to acquire a sufficient supply of bodies of dissecting;

On the first occasion of my joining our nigh excursion, an incident occurred sufficient to awaken in me at least momentary alarm. My lot fell to opening a grave in which the interment of a poor women had taken place. I worked vigorously, and on reaching the frail coffin had no difficulty in breaking back its upper third: but, on stooping down in the usual way … I had to support myself by resting my hands on the chest of the dead; when what was my horror to hear a loud prolonged groan from the corpse … [I realised at length that] the pressure of my weight forced the air in the chest up through the trachea and larynx, and produced the sounds which had momentarily terrified me.[4]

[1] Eoin O’Brien, Conscience and Conflict. A biography of Sir Dominic Corrigan 1802-1880 (Glendale Press, 1880)

[2] Printed List of Medical graduates from Edinburgh University, August 1825, RCPI Archive DC/2/1/9.

[3] Letter Edward O’Kelly to Sir Dominic Corrigan, 26 December 1867, RCPI Archive DC/5/9.

[4] Anon., ‘Reminiscences of the Dissecting Room’, British Medical Journal 1879