Art and Medicine: William Hunter

Last year I posted a series of blog posts looking at diversity in Irish medicine, based on some of the displays at the Heritage Open Day in August 2011. This is the first in a series of posts looking at art and medicine, again based on the Heritage Open Day displays from August 2011. The first post looks at the Scottish obstetrician William Hunter (1718-1783).

|

| Bronze medal of Hunter by Edward Burch, 1774 |

William Hunter was one of the leading anatomists and obstetrical specialists of his age. Born in Scotland in 1718, he studied at Glasgow University and in London under some of the best known anatomists and obstetricians. He set up in practice in London, and attracted many high-ranking patients. In 1761 he attended Queen Charlotte during her first confinement, and the following year was appointed as physician-extraordinary to the Queen. He would attend the births of all her children until his own death in 1783. As well as his private practice Hunter also lectured in anatomy, and undertook a number of important dissections, including many of pregnant women. The source of the bodies used in Hunter's dissections has recently caused some controversy. Don Shelton in an article in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine last year suggested that Hunter, and his contemporary William Smellie, had pregnant women murdered, or at least showed a callous disregard for where the bodies came from, to provide illustrations for their obstetrical atlases. Helen King, in an article in Social History of Medicine, has argued that Shelton's claims raise new questions about how medical history is researched, the rise of the internet and non-professional historians, and the way 'historical truths' are generated and accepted.

Hunter is best remembered for his obstetrical research and publication, which greatly assisted him in his private practice. In 1750 Hunter was able to dissect a full-term human gravid uterus, and determine for the first time the relationship between maternal and foetal blood. The dissections were illustrated by Jan van Rymsdyk, and the art works exhibited. Twenty four years later Hunter published his greatest work Anatomia uteri humani gravid tabulis. It is illustrated with 34 engraving by van Rymsdrk, including the ten from the 1750 dissection.

|

| Illustration from Anatomia uteri humani gravid tabulis |

Following Hunter's death, a draft manuscript for Anatomical Descriptions of the Human Gravid Uterus was found. It was published in 1794 edited by Matthew Baillie (1761-1823), Hunter's nephew, whose education Hunter had overseen.

Hunter was a magnificent lecturer, and as he did not publish a great deal some of his discoveries are only to be found in notes taken by his students during his lectures. In an 1817 biography of Hunter, Joseph Adams (1756-1818) describes him as 'the most perfect demonstrator as well as lecturer the world has ever known'. Hunter began lecturing in London in 1746 offering courses in which 'gentleman may have the opportunity of learning the Art of Dissection ... in the same manner as in Paris', meaning they would practice on a human corpse. In 1760 Hunter planned to give up lecturing but the protests of his students changed his mind. In 1767 he began lecturing in his newly designed anatomy theatre, attached to his house on Windmill Street. The building also contained a museum to house his growing collection of medical specimens and his art collection. After his death this collection would go yo Glasgow University, where it forms the foundation of

The Hunterian Museum.

|

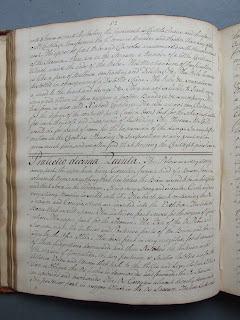

| BMS/32 - An unnamed student's notes from Hunter's Lectures |

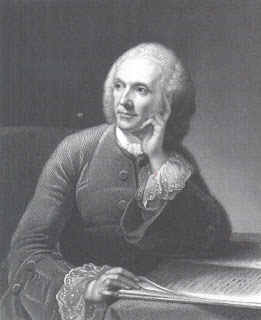

Hunter greatly valued the importance of art to medicine, stressing the importance of accurate and natural plates to illustrate his own works. In 1768 when the King founded the Royal Academy of Art, Hunter was appointed professor of Anatomy. He said of himself that 'I am pretty much acquainted with all the best artists and live in friendship with them.' An important and wealthy figure in London society, Hunter was both patron and subject of the arts. He had a fine collection of art work, a vast library, and a collection of coins said to be second only to the King of France's own. His portrait was painted several times, including by the influential portrait painter

Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792). His likeness continued to appear in engravings into the nineteenth century, confirming his position as one of the 'great men' of medicine.

|

| Engraving of William Hunter by James Thomson, 1847 |