Beyond the ‘lunatic poor’: Class and Insanity in Nineteenth-Century Ireland

Today's post is written by Alice Mauger, who won the poster competition in last year's RCPI History of Medicine Research Award. Alice is a currently studying for her PhD in the Centre for the History of Medicine in Ireland, University College Dublin, she is the holder of a Wellcome Trust Doctoral Studentship. In this post Alice talks about her current research into the provision of non-pauper mentally ill in Ireland in the nineteenth century.

In recent decades, medical historians have proven increasingly attentive to the development of Ireland's mental healthcare system. They have delved into the records of numerous institutions to reveal an extraordinarily rich and varied picture of asylum life. Their studies have recaptured the social background of asylum patients, the treatments they received and their experiences. Among the most exciting discoveries, patients' letters to their families and friends abound with references to asylum life, while medical case notes reveal how psychiatrists discussed their patients, defined their illnesses and attempted to cure them. Despite indisputable progress in reclaiming the history of Ireland's mentally ill and their care-givers, scholarship on Irish asylum patients has focused almost exclusively on the poor.

This tendency arguably reflects a historical reality; during the nineteenth century most asylum patients were poor. In 1817, the state sanctioned the construction and establishment of district asylums for the 'lunatic poor'. These asylums quickly became the largest system of mental healthcare in Ireland and by 1900 accommodated almost 16,000 patients. Conversely, private asylums charged high fees, catered almost exclusively to the wealthy and by 1900 housed only 300 patients. A third kind of institution, the 'mixed' asylum, offered less expensive accommodation to those who could not afford private asylum fees but who were not destitute. Funded by patient fees and voluntary subscriptions, mixed asylums provided care for paying patients and some non-paying patients who were considered 'respectable' but had fallen on hard times. By 1900 mixed asylums had outstripped private institutions and provided care for 400 patients. Growing demand for non-pauper mental healthcare also prompted a decision, in 1870, to admit paying patients into district asylums. However, paying patients accounted for only a very small proportion of admissions to district asylums, making up no more than 3% by 1890.

The proportion of non-paupers in nineteenth-century Irish asylums was therefore relatively small. Nonetheless, exploration of this group reveals the importance of class, gender and religion to contemporary psychiatric thought and practice. My project surveys the records of eight Irish mental hospitals, including the Hospital of St. John of God, Grangegorman and Stewart's Institution in Dublin and the district asylums in Clare, Wexford and Belfast. To date, I have examined the social and medical background of almost 2,000 patients as well as hundreds of psychiatric case notes, patients' letters, annual reports and minute books. My study reveals the impact of factors such as social class and status, wealth, gender and religious persuasion on treatment, care and patient experiences. These factors also influenced decisions made by families when selecting between the three systems of asylum care. For instance, families were often reluctant to commit relatives to district asylums as paying patients because special rules stipulated that they must be maintained, cared for and treated under the same conditions as pauper patients. These measures were intended to guard against anticipated jealousies between pauper and paying patients and extended to diet, living conditions and even clothing. They were perceived by many as ill-suited to those of a higher social status. Moreover, the stigma attached to having a relative in a primarily pauper institution sometimes deterred those who was anxious to assert their 'respectability'.

|

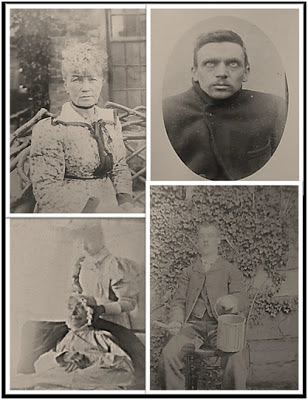

Paying Patients in Richmond District Lunatic Asylum (1885-1900),

Male and Female Case Books, Accessed at the Grangegorman Museum |

|

| Medical Directory, London and Provincial, Scotland, Ireland (London, 1899), p. 2101. |

Aside from affordability, other factors influenced families in their selection of asylum care. Religious persuasion was an important consideration: Catholics were more likely to be committed to a district asylum while mixed and private asylums, which often had a Protestant ethos, catered to the majority of Protestants. Some exceptions to this were St. Vincent's and the Hospital of St. John of God, which were both run by Catholic religious orders. In addition, an asylum's location could influence committal patterns. While district asylums were located in various districts (comprising one or more counties), mixed and private asylums were almost exclusive to Dublin. Nonetheless, patients came from all parts of Ireland to avail of more expensive and comparatively luxurious asylum care.

|

| Medical Directory, London and Provincial, Scotland, Ireland (London, 1892), p. 1844. |

In the late nineteenth century, attitudes towards the mentally ill could also be shaped by patients' social status and in particular their occupational background. Psychiatrists frequently measured non-pauper patients' 'sanity' against their ability to thrive professionally. They recorded men's inability to perform in the workplace, with particular emphasis on clerks and accountants who had failed to balance their books and merchants who had lost interest in their speculations. Failures such as these were regularly identified as both a cause and an indication of insanity. This tendency was indicative of contemporary psychiatric thought on the links between overwork and mental strain. It also reflected a Victorian emphasis on productivity, inherited largely from industrial Britain. Nevertheless, the identification of work-related strain was not just a psychiatric or cultural construct. During the economic depression of the 1880s and 1890s, a significant number of Irish men and women were plagued by financial worries and required respite from managing an ill-fated business or unproductive farm. In some few instances, however, families apparently exploited the local district asylum, committing sane relatives in order to gain control of property or land.

My on-going research has identified the historiographical value of analysing the broader spectrum of social classes who engaged with, and made use of, nineteenth-century Irish asylums. Although admittedly far smaller in number than pauper patient populations, other social classes manifested different traits and responses to their illness, engaged in more complex power struggles with their relatives and care-givers, and, in many instances, derived more freedom and even enjoyment out of asylum life than their pauper counterparts. Furthermore, exploration of smaller mixed and private asylums offers a counterpoint to the harrowing accounts of larger, over-crowded and disease-ridden district asylums which have often monopolised the attention of historians of Irish psychiatry.

Alice Mauger