Guest Post - Blood Letting and Opium: the Treatment of Febrile Diseases in Cork Street Fever Hospital in the Early 1800s

|

| Picture reprinted in annual reports (CSFH/1/2/1) |

This guest post is by Noel Bennett, who completed an MA in Local History in NUI Maynooth in October 2010. Noel's thesis was entitled 'The House of Recovery: Cork Street Fever Hospital, 1804-1854'. The following article is formed from extracts from this thesis.

The early nineteenth century was a period when the medical

profession appear to be baffled by the origin and spread of fever and an era

when physicians in Dublin were as likely to suffer fever infection as their

patients. Their strong belief that the weather was a major factor led to the

collation of the weather conditions by staff in Cork Street Fever Hospital for every day in the first three months of

1816 to an entire year in 1837. In 1837 every physician in the hospital was affected

by fever and two died. The threat posed by fever to the health of Dublin’s

inhabitants in the early 1800s was apparent, as every decade after 1810 saw a

least one serious outbreak of fever, with major epidemics occurring in Dublin

in 1818,1826,1832,1837 and 1847.

Physicians working in Cork Street Fever Hospital were also unsure of

how best to treat many febrile diseases, and lengthy sections of annual medical

reports from this period were devoted to analysis of the merits of various

methods of treatment. The annual report of 1813 contains a lengthy review of

the practice of blood letting which was being practiced by Dr. Thomas Mills in

the hospital. The hospital physicians reviewed the survival rate of his

patients by analysing 2,240 of his cases. They came to the conclusion that

blood letting exerted no influence in rendering the disease less fatal or less

protracted. They concluded their review by stating that they owed it to the

public and the profession not to be silent on the claims ‘so boldly put forward

and so pertinaciously maintained.’

The 1815 report returns once again to the issue of blood letting

with one of the physicians, Dr. John O’Brien, believing that it had a role to

play in the treatment of fever. The other physicians were apprehensive that

even the loss of a small quantity of blood was likely to lead to exhaustion.

O’Brien went on to question the preferred treatment which was to support the

patients strength with ‘enormous’ quantities of wine whose only effect was to increase the

‘determination of blood to the head’ and aggravate the problem it was intended

to cure. Blood letting involved shaving the head of

the patient and washing the head frequently with vinegar and water. Leeches

were then applied to the temples and if this produced no relief, the temporal

artery was opened and four to six ounces of blood removed. Alcohol was still widely used in 1827 when

the board enquired into the quantities purchased. In the first four months of

that year there had been a daily average of 355 patients and thirty gallons of

spirits and 41 dozen of wine of wine had been consumed.

|

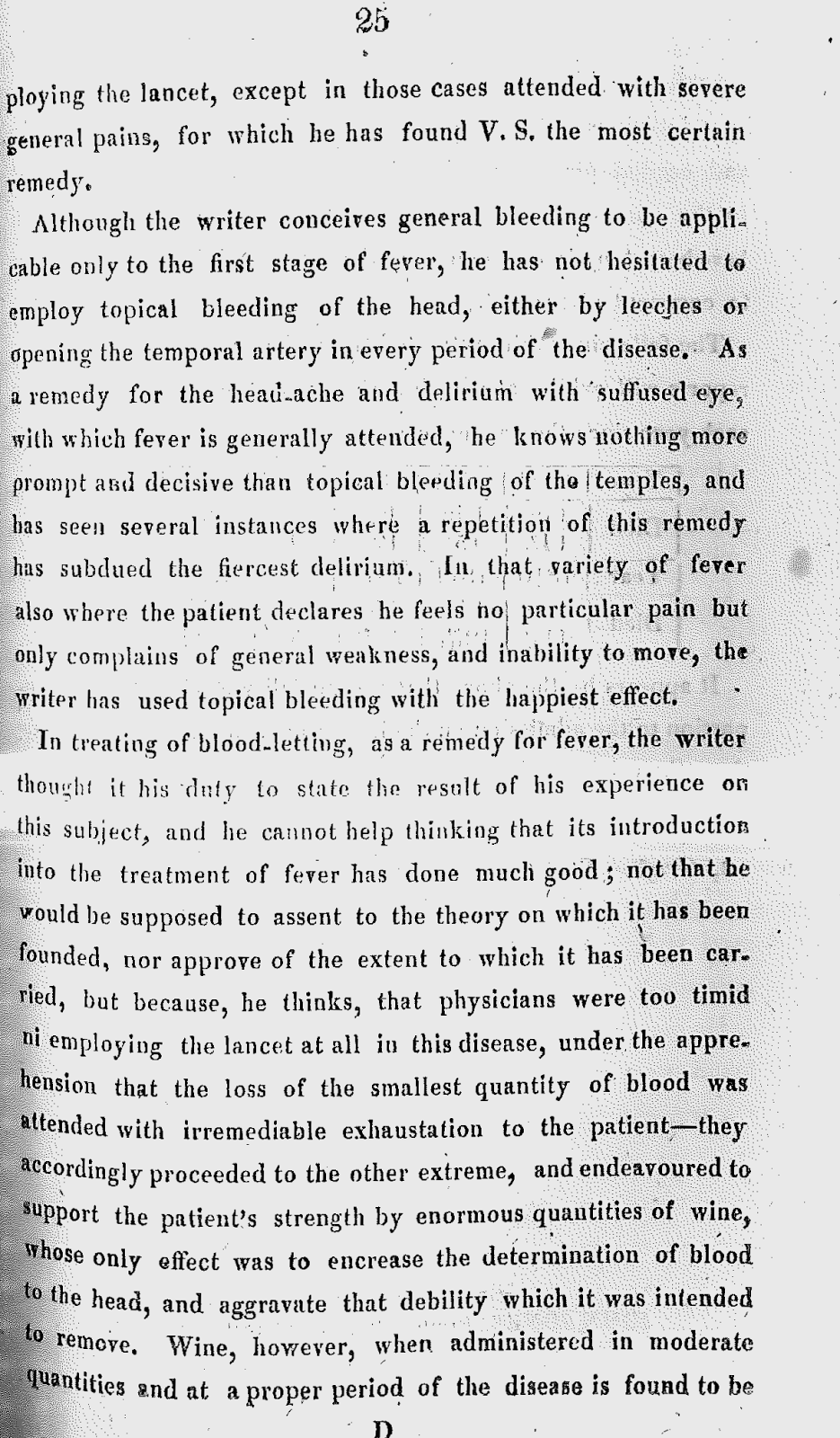

Passage from 1815 Annual Report, written by Dr John O'Brien, concerning blood-letting (CSFH/1/2/1/1)

|

In the 1837 annual report opium is mentioned as a treatment for

patients suffering from typhus and delirium tremens. It was administered in

powder form and described as Dover’s powder. Dr George A. Kennedy was of the

opinion that there was no drug that requires more observation than the use of

opium in the treatment of fever. Wine however was still preferred with an

average quantity of eight ounces over twenty four hours being the recommended

dose.

|

| A scarifying kit, an example of 19 century blood-letting equipment |

The annual reports also contain many suggestions for preventative

measures to stem to spread of fever, which seem more sensible to present-day

eyes. As fever raged in Dublin in 1818, the Government wrote to the hospital

requesting their views on the likely cause and solution. The managing committee

and the physicians both replied separately to the request. The committee

referred to the poor harvests of 1816 and 1817 which they said caused a degree

of distress scarcely to be believed. The lack of employment, scarcity and price

of food all induced a more than usual neglect of cleanliness in the homes of

the poor and in their persons. They suggested that anything that would promote

cleanliness and sobriety among the poor would lead to abatement of the present

epidemic and of fever generally. A copious supply of water would promote this

objective. The physicians emphasised the need for

additional facilities for the hospital noting that patients had to wait days

for admission and some had died during the waiting period. They also noted a

reduction in the number of beggars on the street. It was believed that beggars

contributed to the spread of contagion and the physicians hoped that the evil

of permitting them to be at large would not recur.