Guest Post: Robert Graves' Death Mask

Today’s guest post come from Bryony

Swain, a recent graduate of History from University College London, she had

been volunteering with the UCL Museums and Collections department since October

2014.

While volunteering in UCL’s Museums and Collections department I have been cataloguing a brilliant collection they

have of life and death masks, which were collected by the phrenologist Robert

Noel in the 19th century. Phrenology is the theory that measurements

of a person’s skull can identify character traits. Noel used the masks in an

attempt to prove his theories on phrenology. Today phrenology is discredited, but

during the 19th and early 20th century it was very

popular among scientists.

Noel divided his collection into

categories; ‘intellectual’ males, ‘ladies displaying intellectual and moral

qualities’ and ‘criminals and suicides’, in order to illustrate that those of

intellectual and moral standing had a different skull to criminals and those

who committed suicide.

Whilst researching the individuals

behind the masks I came across Robert James Graves (1796-1853), a distinguished

Irish physician and surgeon.

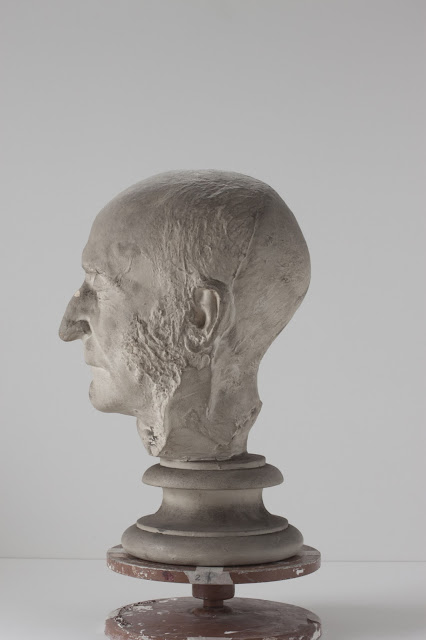

|

Graves Death Mask

(Reproduced by permission of UCL Museum and Collections) |

Graves obtained a medical degree from Trinity

College, Dublin in 1818. He was quite the traveller and the artist Joseph

Turner accompanied him for some of his European journeys. Whilst in Austria,

Graves was arrested and accused of being a spy because they did not believe an

Irishman could speak such good German! His adventurous life is further captured

in the story about a boat trip to Sicily. During a storm the boat came into

difficulty with the crew about to abandon ship. Graves made a hole in the

lifeboat leaving all on board to the same fate and managed to fix the problem

and got all on board to safety. Graves returned to Ireland and his impressive

medical career began. He became President of the Royal College of Physicians of

Ireland in 1843.

Graves clearly had a remarkable

life. In his book, Noel adds a personal element to his biographical history.

For instance, Noel recounts how Graves asked his students to only speak about

their patients’ illnesses in Latin so to not distress them. For Noel this

accounts for the phrenological measurement of “Benevolence”. Furthermore, he

writes how Graves “took great interest, too, in the wards devoted to children, and the

judicious and kindly treatment of the juvenile patients: and this fact agrees

with the finely curved and prominent occiput." This is an example of

Noel using aspects of a person’s life to subjectively support his theories, however

it does give a deeper insight into Graves’ life.

A lot can also be learnt about

the shape of Graves’ head. Along with measurements Noel notes, "The cast of

this head is large in every direction. It belongs to what anthropologists call

the dolichocephalic class. The frontal lobe, the seat of the intellect, is very

large; and… the seat of love for children is particularly prominent.” In

phrenological terms, Graves clearly had a good head! Although the scientific

accuracy of Noel’s work is questionable, it does give

personal information about historical figures, like Graves, which would be left

out of more formal histories.

|

Side view of Graves' Death Mask

(Reproduced by permission of UCL Museum and Collections) |

Unlike other individuals in the

intellectual category Noel did not know Graves personally. He explains how he acquired

Graves’ death mask from the sculptor Bruce Joy, “who has executed a bust of Dr. Graves, to be

placed, I believe, in the University Building of Dublin. This copy of the

post-mortem cast, which Mr. Joy had received for the execution of his work, had

been given to me by him." I believe that this may well be the statue

of Graves that is in the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland, which is

certainly the work of Bruce Joy. Hopefully the two can be reunited for display!

|

| Statue of Robert Graves by Bruce Joy in RCPI |

Bryony Swain

UCL Museum and Collections Deparment