Guest Post: Sir John Crofton, the Irish Pioneer in the Treatment of Tuberculosis

By

Chris Holme

By

Chris Holme

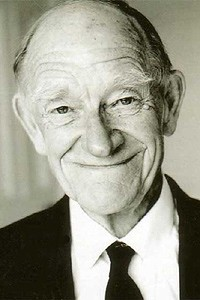

He

scarcely rose above the five foot mark but ranks among the loftiest giants of

20th-century medicine.

Sir

John Crofton led the Edinburgh team which found the world’s first 100% cure for

tuberculosis (TB). Although born and raised in Dublin, he remains largely

unrecognised in Ireland. He died in 2009 but his memoirs Saving Lives and Preventing Misery shed fresh light on growing up in a privileged

Anglo-Irish family where his pals included the children of WB Yeats and James

Stephens.

Born

in Dublin in 1912, John’s father William Mervyn Crofton was a doctor and

lecturer at University College Dublin. Over Easter 1916 they went to stay with

relatives in Carlow – this was fortunate because the house at 52 Merrion Square

was caught up in crossfire and five bullets peppered Crofton’s nursery.

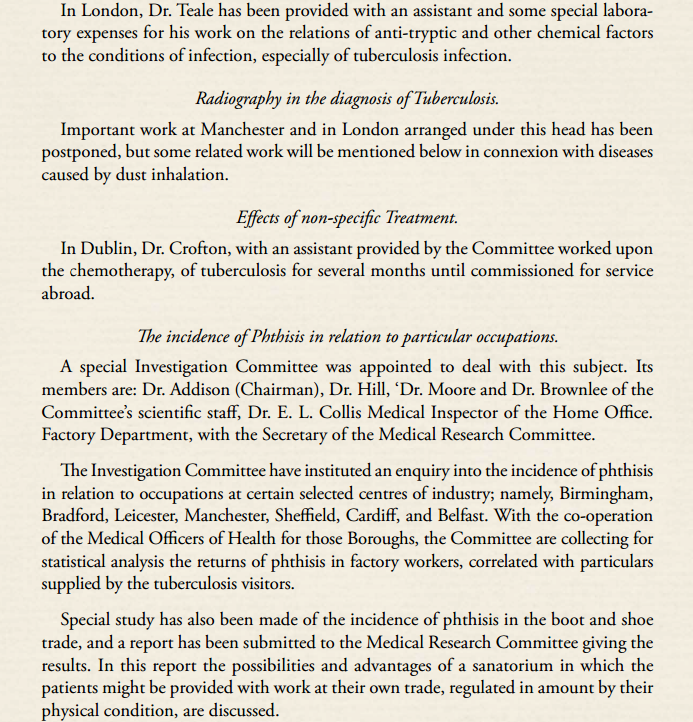

Curiously, William Crofton is mentioned briefly in the first annual report of the Medical Research

Council (then the Medical Research Committee)

as working on “chemotherapy” for tuberculosis, the very subject his son

was to revolutionise 40 years later.

Aged

nine, Crofton was packed off to the Baymount preparatory school, Dublin. He

then attended public school in Tonbridge School, Kent, England, and Sidney

Sussex College in the University of Cambridge, where he wasn’t an academic star

but a good climber. There is a route named after him in the Cairngorms still

rated ‘severe’ for climbers with all modern equipment. Crofton first conquered

it in 1933 in short sleeves and hobnail boots.

|

Extract from the first annual report of the Medical

Research Council, containing mention of Dr Crofton's

work on chemotherapy

|

Crofton

matriculated at Cambridge in 1930, going on to earn an MB in 1937 and MD in 1947. It was his experience as

medical officer in the war that shaped him. He courted his wife Eileen, a

fellow doctor, when they were both stationed outside Belfast in 1945.

Crofton’s

approach to medicine was the opposite of the autocratic and opinionated style

of his father. He helped engineer evidence-based medicine using objective

assessment provided by randomised trials. Following his return to London after

the War he was involved in the Medical Research Council’s trial of streptomycin

- the first effective drug against tuberculosis.

In

1951 he was appointed to the chair of tuberculosis at Edinburgh University after

an interview over a long, liquid lunch

at the New Club which he said triggered his intrinsic Hibernian garrulity.

Scotland was then in the middle of a rising epidemic of TB, particularly among

young women. The NHS service was a shambles. One consultant combined misogyny

with sadism telling girls on his ward “You are all rosy red apples, rotten to

the core.”

Crofton

changed all that. He built his own team and made scrupulous use of bacteriology

for keeping close tabs on how the TB bugs changed in patients. Instead of giving

one drug then another, the Edinburgh doctor took the revolutionary step of

using all three from the outset.

Rising

TB notifications in Edinburgh were halved between 1954 and 1957 – a feat not

achieved anywhere before or since. Their success was so spectacular that many

did not believe them. It took one of the

first international trials, organised via the Pasteur Institute in Paris, to

establish the Edinburgh method as the gold standard for treating TB.

Crofton’s

warmth, modesty and humanity were predicated on his enduring faith in people

rather than organisations. He was happier on the bus than in a limo and preferred

sandwiches in second class to plush dinners in the dining car. Nurse colleagues

remarked that he would always stand up to offer a handshake when meeting patients

and also stay late to write personal references to help them overcome the stigma

facing TB survivors on their return to the outside world.

His

memoirs – written for his family rather than a wider audience - chronicle his

later career, including a frank admission of his own two-year battle with

clinical depression. Crofton continued tirelessly campaigning on TB and tobacco.

As a co-founder of ASH (Action on Smoking and Health), he was delighted that Ireland led the way in banning

smoking in public places.

Although more

steeped in academic writing, he learned the skills of a tabloid journalist in a

book for TB health workers—now translated into dozens of languages.

Crofton’s

legacy still inspires. One of his disciples, Tom Frieden, director of the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, said in a tribute that the principles of combination chemotherapy not

only revolutionised treatment of TB but also underpin many treatments now used for

cancer and HIV.

Chris Holme is a former Reuters

Foundation fellow in medical journalism at Green College, Oxford. He now blogs

at www.historycompany.co.uk