Guest Post: 'Something for the mental defectives of the west': Establishing a centre for the intellectually disabled at Bohola, Co. Mayo.

Today's guest post is by David Kilgannon who, earlier in the year, won our Kirkpatrick History of Medicine Research Award. This post, based on his winning, presentation looks at the plans to establish a centre for the intellectually disabled at Bahola in County Mayo.

The Department of Health’s file on the efforts to establish a centre for the intellectually disabled in Bohola, a small village outside Foxford in Mayo, is a fascinating collection for those interested in the history of Irish disability provision. Indeed, with its late 1960s narrative of philanthropic American benefactors and valiant voluntary efforts in the face of an entrenched bureaucratic system, the case of Bohola frequently borders on the cinematic. Regardless of the dramatic colour associated with this case, the efforts to establish a residential centre in this Mayo village present a telling insight into the wider priorities that shaped service provision for the ‘Mentally Handicapped’ in 1960s Ireland.

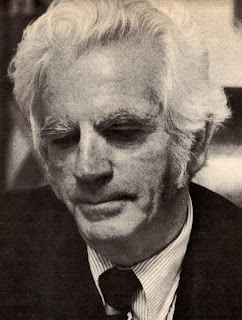

|

| Paul O'Dwyer |

The story begins with Paul O’Dwyer, the Irish American politician and lawyer. O’Dwyer was from a

prominent New York immigrant family; his older brother was William O’Dwyer, who served as Mayor of New York from 1946-50.[1] Paul was himself a member of the New York City Council, and an unsuccessful Democratic candidate for the US House of Representatives, as well as a founding partner in the Manhattan legal firm O’Dwyer and Bernstein. His 1998 New York Times obituary praised his social sensibility and acute identification with the city’s ‘indigents and immigrants, progressives and underdogs … O’Dwyer impressed successive generations as an eloquent battler in the name of conscience.’[2] Having emigrated from his native Bohola in 1925, in 1967 O’Dwyer decided to donate his ancestral homestead to a newly formed group, the Mayo Association of Parents and Friends of Mentally Handicapped Children, for the establishment of a training centre for the ‘mentally retarded’ children of his native Mayo.[3] He proposed to donate his family home and the associated land, alongside carrying out a fundraising campaign in New York to provide finance the establishment of a new institution at the site.

O’Dwyer’s Bohola homestead had a number of advantages as a location for a new institution. Provision of services in Mayo was deficient, as the nearest residential centres were Cregg House (for girls) based outside of Sligo town and Kilcornan House (for boys) based in Clarinbridge in Co. Galway. Compared to these institutions, Bohola also appeared a strong prospect. Cregg House in Sligo had to be created from scratch for the team of nuns from the La Sagesse order in Liverpool, from finding a site, buying it, agreeing on building plans, negotiating on the plans and organising construction.[4] In Galway it meant the restoration of the crumbling remnants of Kilcornan House, which had first been produced by the famed Victorian Architect George Papworth for the local landowners, the Reddington family in 1838. By the time of its renovation in the early 1950s, the main house had been unoccupied for nearly 30 years, and a large proportion of the floors, the roof and a number of walls had to be repaired; alongside the replacement of a number of the outer buildings that surrounded the house, which required extensive reconstruction.[5]

|

| Kilcornan House, c.1900 |

The Bohola project, therefore, with its small ‘two story, three bedroom house standing on four acres of good ground, backed by an initial endowment of over £9,000 from O’Dwyer’ alongside his commitment to raise more funds among the Irish American community in New York, was an inviting prospect.[6] As in other institutions, the existing homestead could have been converted into an office space, while the remainder of the site could have been used for the placement of a small institution. Unsurprisingly, the Mayo Association was eager to proceed.[7] Throughout 1968, the local committee of the Mayo Association worked to raise awareness of ‘Mental Handicap’ and funds for the Bohola centre, while O’Dwyer did the same in the US.[8]

|

| Jack Lynch |

Yet, a letter from Taoiseach Jack Lynch to the Minister for Health Sean Flanagan in July 1968 was scornful of the Mayo initiative. Lynch condemned both O’Dwyer and the Mayo committee for failing to liaise with the Department of Health before beginning their fundraising efforts. Lynch also queried O’Dwyer’s motives, as he suspected that the Irish-American’s ‘own interest in the use of his ancestral home [was] for a prestige and philanthropic purpose’ in the United States.[9] The remainder of Lynch’s letter called for the project to be investigated further before proceeding. An investigation was then sponsored by the Department of Health, with the completion of a report by Dr. Stanley, from the British Training Council for Teachers of the Mentally Handicapped, in November 1968. Dr. Stanley highlighted the geographical disparity of provision for the intellectually disabled in the west of Ireland. After visiting Cregg House in Sligo, the report noted how this nearest institution was: 45 miles away, could cater for only girls, and already had a ‘substantial waiting list for admission from other counties as well as Mayo’. It also highlighted physical challenges within the existing house at Bohola, such as how ‘there is grass growing from the guttering.’ The report stated that it would not recommend the Bohola project due to its report location, but concluded that ‘This I do in spite of my belief that there is a case to be made for extending the facilities which serve this part of the

country.’[10]

Dr. Stanley’s report represents a fascinating description of Irish disability services, produced from the perspective of a British official. Stanley’s nullification of Bohola on grounds of location was, however, incongruous within the context of mid-twentieth century Irish disability services. Kilcornan house outside Clarinbridge in County Galway, for instance, was as isolated as the Bohola site. The main house was a kilometre away from the nearest public road, while Cregg House was nearly five kilometres from Sligo town. It is within the post-report meetings, held between O’Dwyer, the Mayo Association and the Department of Health, that we learn the true obstacle to the Bohola project - staffing. Departmental officials first met with representatives from the Mayo Association in August 1968 to discuss the proposed institution. This meeting is telling of the department’s priorities, as it appears predetermined from the officials’ comments that the new institution at Bohola should be run by a religious order. The minutes detail how, for example, the Bohola project would become costly as ‘Allowing for the provision of a convent … and other ancillary services the capital investment required to provide a viable mental handicap centre could easily run up to £250,000.’[11]

|

| Bahola Parish Church |

This focus on religious orders to provide care presented a number of problems to groups like the Mayo committee, the principal challenge being recruitment of an order. As Louise Fuller and Tom Inglis both note, the seemingly inexorable decline in Irish religious vocations had already begun by the late 1960s.[12] However, even during the 1950s, religious orders appeared reluctant to become involved with intellectual disability issues.[13] Staffing represented the central contention between the Department and the Mayo organisation’s efforts. Following the completion of Dr. Stanley’s report, Minister Flanagan agreed to meet with O’Dwyer during a trip to Ireland. By the end of the meeting O’Dwyer had been persuasive, as Flanagan had agreed to the provision of a home at Bohola, but with the condition that ‘provided it could be established that the staffing problems could be overcome’.[14]

The Bohola initiative to establish a centre for intellectually disabled children was abandoned in late 1968, as it became clear that the local association was never going to be able to satisfy the Department’s stringent ideas around how such an institution should operate. The land, and funds raised, were then returned to O’Dwyer. An anonymous member of the Mayo committee spoke to the Western People newspaper about the association’s efforts, describing the whole process as a ‘miserable experience for all of us’. The account described how a ‘green committee’ of committed parents had set out to pioneer help for ‘mentally handicapped children in Mayo’, but had repeatedly struggled to satisfy the Department’s demands around the correct way to do things.[15] This way, in the late 1960s, was for the Department to lead the project through religious channels, not the other way around. The Mayo Association would eventually become Western Care, which is now a significant provider of services to those with an intellectual disability in County Mayo.[16] O’Dwyer continued to press for use of his family homestead in Bohola, and the land eventually became part of the Cheshire network of services for the physically disabled. In failing to establish a centre at Bohola, this case file offers a tantalising insight into the wider dynamics at play in the provision of services for the intellectually disabled in 1960s Ireland, and highlights how there is a need for so much more work on this underserved facet of Irish history.

David Kilgannon

Wellcome Trust Researcher

NUI Galway

References

[1] William O’Dwyer, Beyond the Golden Door (New York, 1987), p. 228.

[2] Francis Clines, ‘Paul O'Dwyer, New York's Liberal Battler For Underdogs and Outsiders, Dies at 90’ The New York Times, 25 June 1998.

[3] ‘Two schools for retarded children’ Connacht Telegraph, 12 October 1967, p. 10.

[4] ‘Report: Tenders for building works at the home and school of the Immaculate Conception, Cregg House, Sligo’, National Archives of Ireland H26/22/1.

[5] Dr. Kevin McCoy, Report of Dr Kevin McCoy on Western Health Board Inquiry into Brothers of Charity Services in Galway (Galway, 2007), p. 55.

[6] Tatler Two, ‘People & Places’ Western People, 19 October 1968, p. 6.

[7] Ibid.

[8] ‘Residential college for Moderately Handicapped Children’ Mayo News, 10 February 1968, p. 5.

[9] Letter, Jack Lynch to Sean Flanagan, 18 July 1968, National Archives Ireland 2000/6/645.

[10] Dr. Stanley, ‘Report on Bohola’ 26 November 1968, p. 3, National Archives Ireland 2000/6/645

[11] ‘Minutes of meeting in connection with Bohola’ 17 August 1986, National Archives Ireland 2000/6/645.

[12] Louise Fuller, Irish Catholicism since 1950: the undoing of a culture (Dublin, 2004), p. 159; Tom Inglis, Moral Monopoly: the rise and fall of the Catholic Church in Modern Ireland (Dublin, 1998), p. 212.

[13] See - ‘Mental Defective Institutions under the Care of the Hospitaller Brothers of St. John of God’ 26 September 1952, National Archives Ireland H39/25.

[14] ‘Minutes of meeting in connection with Bohola’ 17 August 1967, National Archives Ireland 2000/6/645.

[15] Tatler Two, ‘People & Places’ Western People, 19 October 1968, p. 6.

[16] John O’Dea, ‘Foreword’ in Liam MacNally (ed.) Western Care: Celebrating 40 Years (Castlebar, 2007), p. xiii.