Guest Post - Theories on the causes of fever in early 19th century Dublin

This is the second guest post is by Noel Bennett, who completed an MA in Local History in NUI Maynooth in October 2010. Noel's thesis was entitled 'The House of Recovery: Cork Street Fever Hospital, 1804-1854'. The following article is formed from extracts from this thesis. Noel's first article can be viewed here.

In

the early years of Cork Street Fever Hospital, which opened in 1804, medical

staff were constantly trying to comprehend the reasons behind the spread of

various febrile diseases in the poor neighbourhoods of Dublin. Of these

diseases typhoid, malaria, scarlet fever, measles and dysentery were primarily

responsible for many admissions to the hospital in the early 1800s.

|

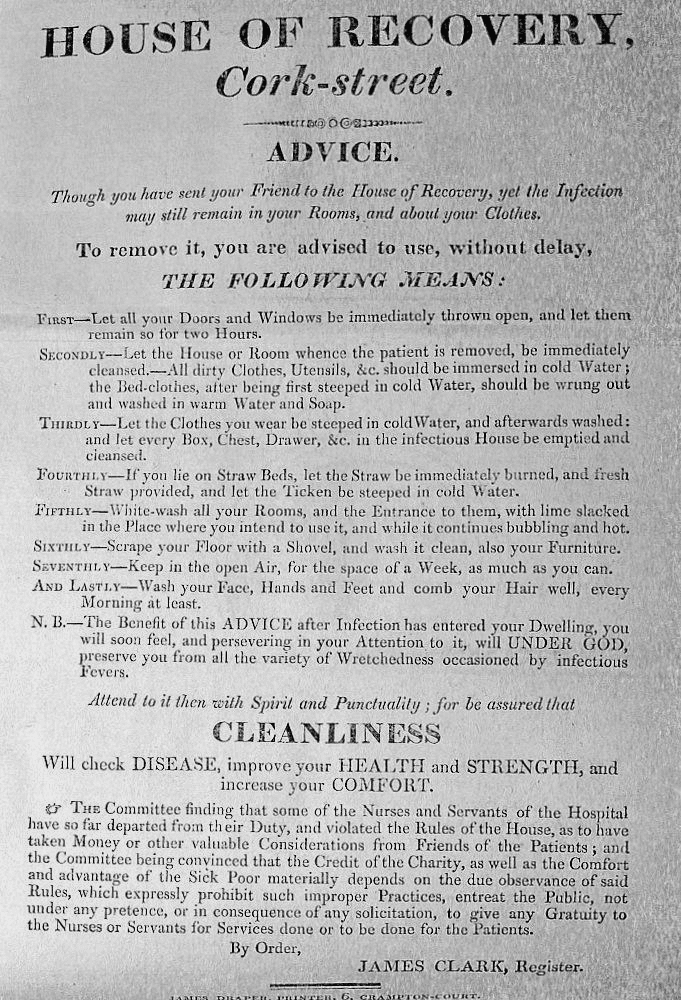

Advice to relatives and friends of patients in Cork Street Fever Hospital, printed in the 1813 Annual Report

(CSFH/1/2/1/1) |

The

problem for the medical staff in Cork Street was attempting to understand the

causes of fever. Many likely causes were identified and these ranged from the

direction of the wind to the issue of cleanliness or the lack of it. In their

annual report of 1806 the death of a recently employed nurse-tenderer is

mentioned and the likelihood that her death was hastened by her lack of

experience in dealing with fever patients. Cleanliness, the authors emphasise,

is the greatest defence against fever. They contend that contagious diseases do

not spread in the upper ranks of society due to ‘their frequent ablutions and

change of apparel.’ The treatment of fever was not passive and the homes of

their patients were often whitewashed either by hospital staff or by the Sick

Poor Society of Meath Street.

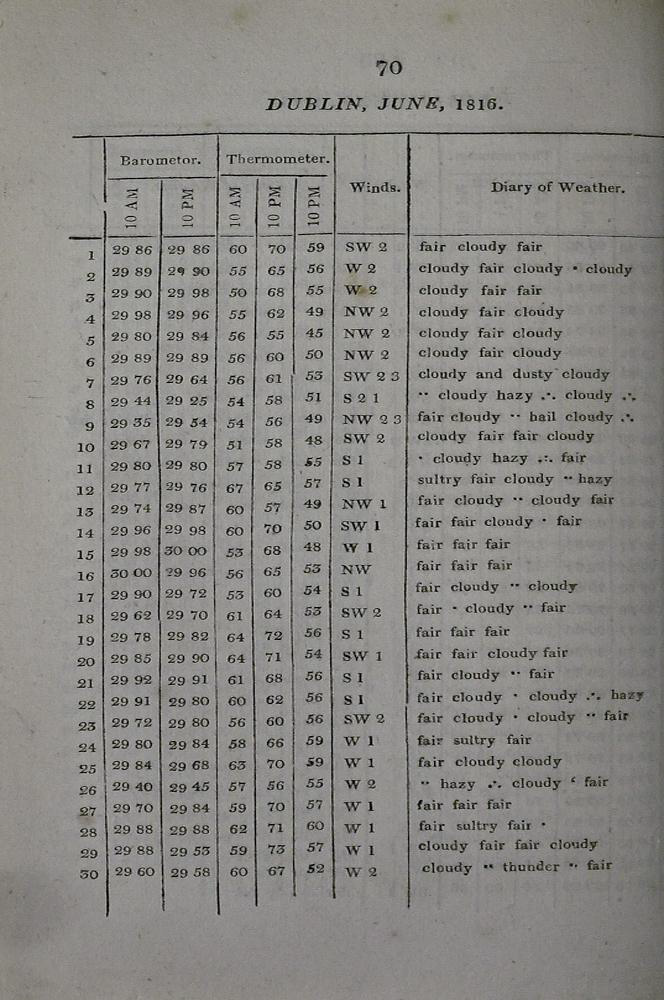

In the 1807 annual report, the spread of fever is attributed to the prevalence of easterly winds. The report contains an observation which

states that the nature of an epidemic is much modified by the contribution of

the atmosphere. This belief is also evident in the hospital’s annual report for

1816, in which the weather conditions of every single day in the first three

months of the year are recorded. The barometer and thermometer readings at

specified times of the day, direction of the wind and a brief description of

the overall weather conditions are all noted.

|

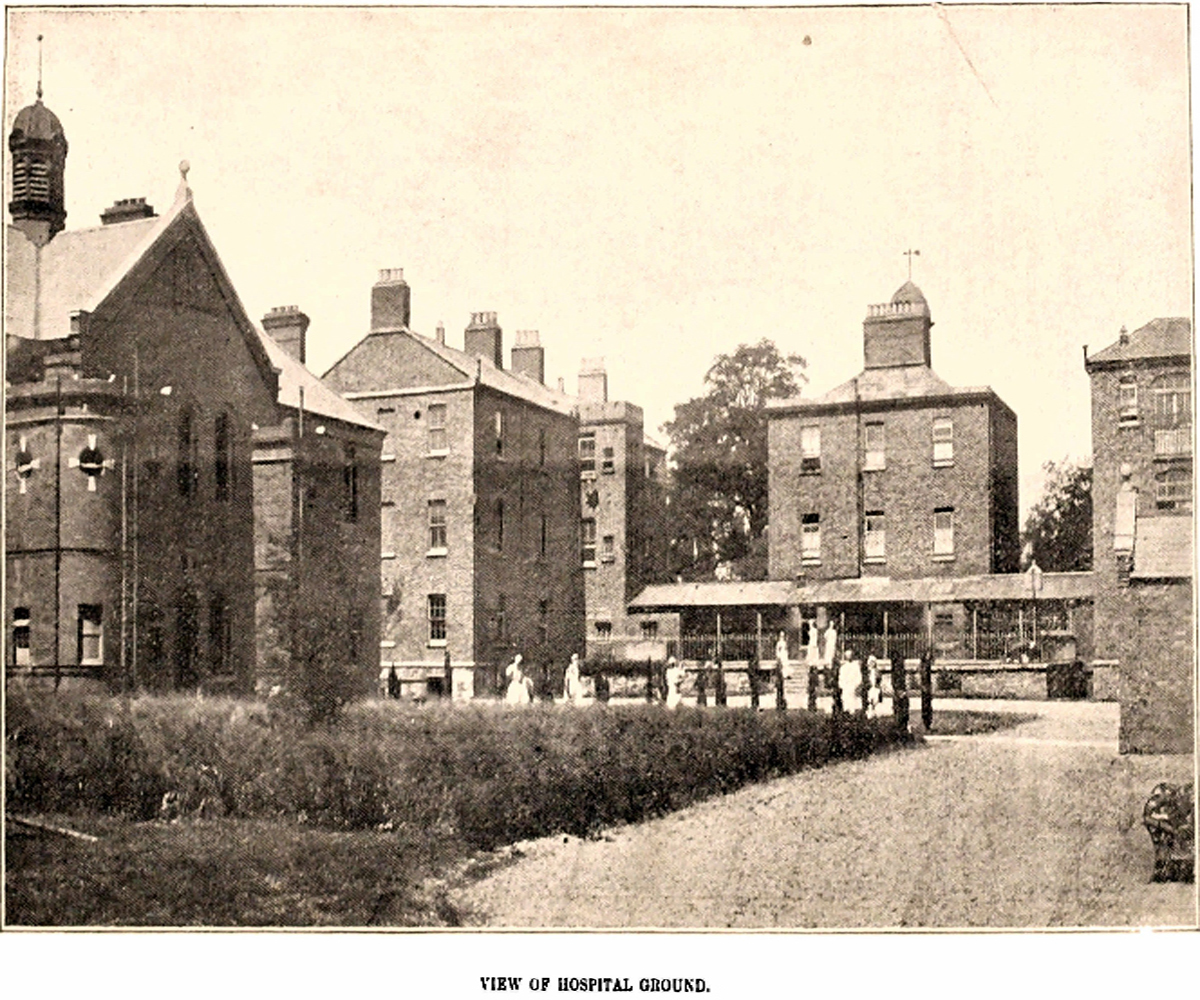

| Late 19th century photograph of the hospital ground, reprinted in annual reports (CSFH/1/2/1) |

This belief was also expressed by Dr William Stoker,

physician in Cork Street, in his 1835 review of the epidemic diseases of

Dublin. Stoker’s review commenced by examining the cholera epidemic of 1832. In

1831 there had been a trickle of cholera cases treated in the hospital but by

1832 the city was experiencing what was then the worst epidemic of the century.

In Dublin alone cholera affected 11,000 with the death rate put at 5,273

persons.

Cholera had spread across Europe through the shipping ports. It reached Quebec

where its origins were attributed to an Irish emigrant ship.

Stoker was of the opinion that ‘east and northeast winds

blowing from an extensive strand and victual soil during the time of neap

tides’ added to the extent of the problem. This affected people living on the

lee shore many of whom were predisposed by ‘want of necessary support or by

despondence from the miserable state of trade.’ The first outbreak that year

occurred during Lent, and he believed that fasting contributed to the problem.

He also stated that from his conversations with Roman Catholic and Protestant

clergymen, the fever was confined entirely to members of the Catholic faith.

|

| Extract from a weather report, printed in the 1816 Annual Report (CSFH/1/2/1/1) |

Cork Street Fever Hospital refused to treat the victims of

cholera during this epidemic, believing it to be so infectious as to threaten

the lives of other patients. The board actually obliged Dr. Stoker to retire

for ignoring this rule despite his thirty two years of service there. Other

Dublin hospitals also refused on the same grounds. A public meeting of medical

officers was held in the coffee room of the Royal Exchange to demand that

cholera patients be treated in fever hospitals. Various proposals including one

demanding a posse of police to force hospitals to admit cholera patients were

put forward. This meeting referred to the ingratitude of Cork Street for their

outrageous treatment of Dr Stoker. In the event cholera patients were treated

in Grangegorman hospital which was referred to as the Dublin Cholera Hospital.

Noel Bennett,

MA in Local History,

NUI Maynooth