Guest Post: View from a Researcher

Our guest post today come Maire Fox, a PhD candidate at St John's University, studying the practice and pedagogy of medicine in early 19th century Ireland.

For seven weeks this summer, I had the privilege of conducting archival research in RCPI’s wonderful Heritage Centre. I was able to review numerous period volumes and manuscripts, with particular attention to materials documenting the development of specialisation within the medical profession. My research examines the influence of socio-medical factors on medical practice and education during the period – specifically on the foundational role of anatomical dissection to the fields of diagnostic medicine, surgery and pathology. Notable in this regard were the enactment of the Anatomy Act of 1832 (which provided a legal pipeline of bodies for anatomization in medical schools) and subsequent legislative and regulatory interventions in medical education and licensure.

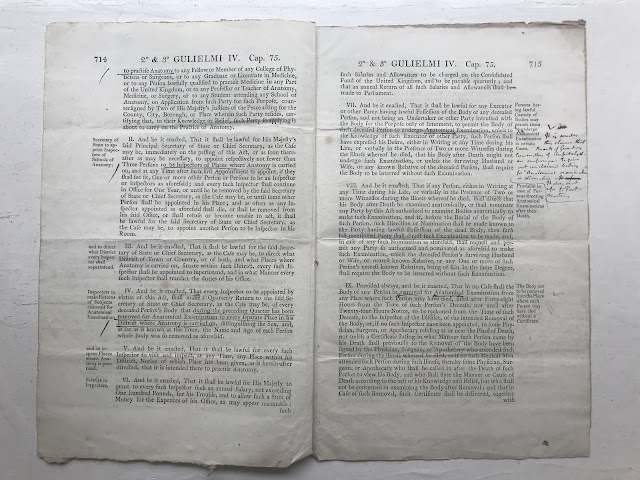

Among the most interesting collections I reviewed at RCPI were the personal papers of Sir Dominic Corrigan, a prominent Irish physician of the period and a past President of the College; the papers include a copy of the 1832 Anatomy Act annotated by Corrigan. In addition, the Heritage Centre contains period volumes of testimony, investigations and reports of Parliament’s Select Committees on Anatomy (1828) and Medical Education (1834). These volumes address the then current state as well as the future of medicine in Britain – subjects of interest to Parliament because of calls to redress nepotism rampant in the process of appointing physicians to the College and as Professors of Medicine.

|

| Corrigan's annotated copy of the Anatomy Act |

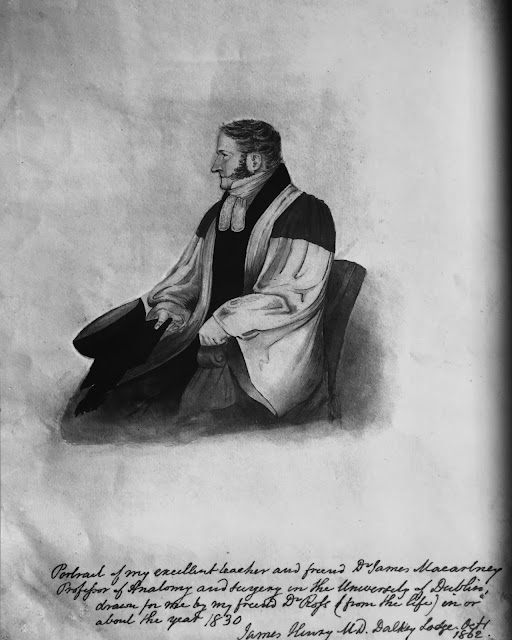

Corrigan himself sought a professorship in 1841 and RCPI holds his application as a “Candidate for the Professorship of the Practice of Medicine in the School of Physic in Ireland.” Following in the footsteps of other great physicians (such as James Macartney, who himself applied for a Professorship of Anatomy in 1813), Corrigan’s successful application demonstrates that the quality of medical education in Ireland was held in similar, and sometimes greater esteem than that in Oxford and Edinburgh. In addition, the components of his application offer a synopsis of the ideals valued by physicians at that time. Corrigan believed that the successful candidate for a Professor of Medicine should excel in hands-on experience, contributions to the field through research and publication, and teaching ability.

|

| Sketch of Dr James Macartney by Dr James Henry |

As to the first requirement, Corrigan stated that the candidate should be “in possession of such an extensive field of Hospital Practice as will furnish him with the means of constantly maintain a practical acquaintance with disease in all its varying types and forms, so as to enable him to deduce his instructions from direct observations.” Hospital practice during the mid-19th century was key to student instruction. Far from earlier iterations of medical education which relied heavily on treatises, Corrigan (and his contemporaries) believed that a successful medical student should learn both through practical application as well. Corrigan himself was intimately acquainted with several hospitals in Dublin – he was a Physician at the Sick Poor Institution (Dispensary), the Jervis-street Hospital, the Hardwicke Fever Hospital and the Whitworth Chronic Hospital. Medical students had generally found value associating with hospitals, as evidenced by student notebooks and lecture materials (also contained in RCPIs archives) which reflect a pattern of hospital visitation for pedagogical observation and practice.

|

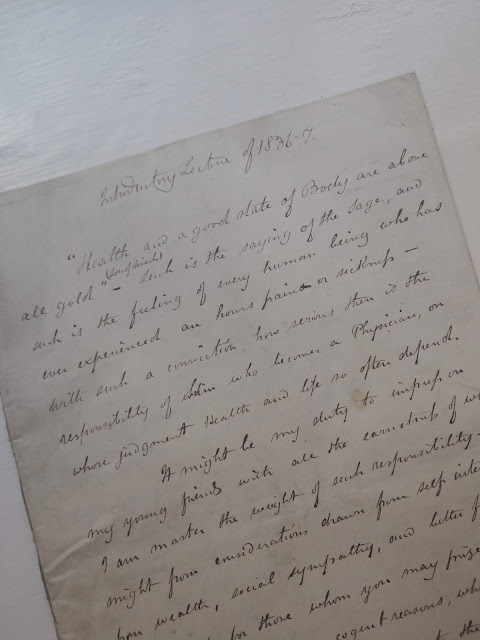

| Corrigan's notes for his Introductory Lecture in 1836 |

In the second category, Corrigan argued that the successful candidate “shall shew by his writings that he has not failed to avail himself of the opportunities which he has possessed, to contribute to the improvement of his Profession and the advancement of the science of Medicine.” The field of medicine during the mid-19th century was experiencing a renaissance, rapidly expanding as the definition of doctor was changing with the times. Physicians and surgeons were expected to be more involved in their own knowledge acquisition and transfer, oftentimes studying minute parts of the body (e.g., Richard Butcher produced extensive works on the excision of the knee joint) or very specific illnesses. At the time, Corrigan was widely published in multiple medical journals including The Lancet, Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal, and most extensively in the Dublin Journal of Medical Science. His publications covered topics such as cirrhosis of the lung and functional diseases of the heart as well as early sociomedical studies into fever in Ireland. We can see from Corrigan’s application that he was especially revered in the field of pathology (which at the time was a sub-set of anatomy, often referred to as morbid anatomy). Indeed, Corrigan’s application was supported by the French pathologist, G. Andral, one of the most highly revered pathologists of the period, and by Robert Graves, a physician and editor of the Dublin Journal of Medical Sciences.

|

| Sir Dominic Corrigan |

Corrigan’s third stipulation is that the successful candidate “possess the capability of Lecturing, or of conveying to others the information which he has himself acquired.” Corrigan had lectured in the medical classroom for several years and trusted that the Board would form opinions of a candidate’s ability “from personal inquiries among the medical classes of Dublin.” Corrigan’s skill as a lecturer can be seen through several of his introductory lectures on anatomy, also housed in the RCPI collections. In his 1836-1837 Introductory Lecture, Corrigan begins with grandiose statements about the responsibilities of doctors and the countenance with which they must operate. As the lecture continues, he provides an overview of the body – breaking it down into categories of systems and organs. He offers a brief overview and explains how each category will fit into the course of study and why it is imperative that students learn this material. Perhaps most interesting is that Corrigan speaks as an idealist as well as a pragmatist; he addresses his students as being responsible for great tasks and great ideas while also conveying that the science itself can be fruitless and often difficult (with no answers).

I am most grateful for the opportunity to review the materials in RCPI’s Heritage Centre. I thank the institution and the excellent archivists who assemble, catalogue and maintain the collection – and the physicians (including Corrigan) who had the foresight to donate their personal archives for future reference. The history of Irish medicine is an understudied area (compared to British medicine generally), but it merits attention because of the unique context of Irish culture and the excellence of Irish medical education. RCPI’s Heritage Centre holds a key to furthering investigation of this area of historical inquiry.

Maire Fox