Guest Post: What Happened to Dr. Dickson, First Librarian of Dun's Library?

This week is Library Week Ireland. To coincide with this, the following guest article written by Michele Holmgren sheds light on the life of the first librarian appointed by the College, Dr Stephen Dickson, following his departure from RCPI and Ireland. Michele has a PhD in Canadian Literature from the University of

Western Ontario, and a Master’s Degree in Irish Writing from Queen’s University

Belfast. Michele is currently an Associate

Professor who teaches Early Canadian Literature at Mount Royal University,

Calgary, Alberta, Canada, and is President of Canadian Association for Irish Studies (2012-2015).

|

Dun's Library, Royal College of Physician of Ireland

Dr Stephen Dickson (1761-1799), the first librarian of the Trinity Medical School, is known today mostly for losing many of the library's rare and valuable books, after which he "disappeared from Dublin".[i] Already dismissed from his position as King’s

Professor in 1797 for neglect of duties[ii], he

was then deprived of his Fellowship of the College of Physicians for having

‘been absent from the meetings of the College for two years without leave.”[iii] It is not surprising that he was unable to

attend meetings in Dublin, given that he had emigrated to Quebec in October,

1798.

Dickson's time in Canada was very brief, but he made a contribution to early Canadian literature: a handsomely bound long poem published by John Neilson, entitled The Union of Taste and Science (1799).[iv] The poem appears to be part of Dickson's attempt to repair his fortunes: towards that aim he also produced a small pamphlet, Considerations on the Establishment of a College in Quebec for the Instruction of Youth in Literature and Philosophy (1799), in which he stated: "I can only propose in the infantile and unendowed state of the college of Quebec, the humble but zealous offering of my own exertions... Were I not apprehensive that without this part of my proposal every thing else might end in languid speculation, I should never have risqued [sic] incurring the suspicion of self-sufficiency, (which I deprecate as truly foreign from my feelings).[v]

|

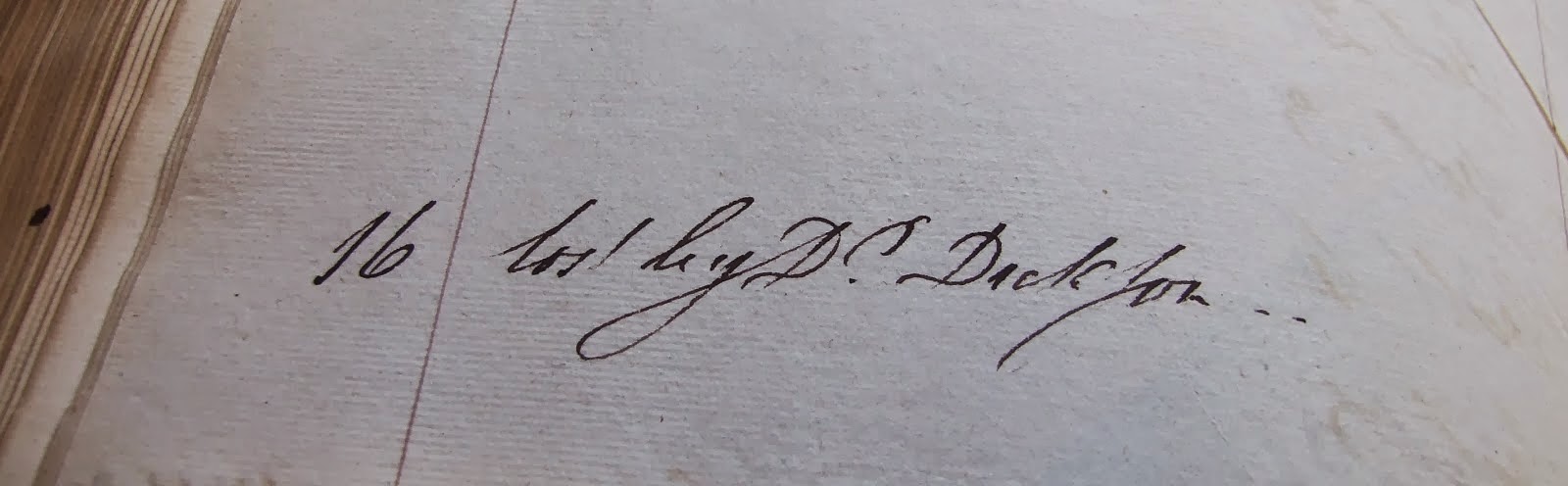

Entry in a catalogue of books of Sir Patrick Dun's Library from 1800, which

notes those books which had been 'lost by Dr Dickson' (RCPI/8/1/2/1/2)

|

In

spite of advertising his many qualifications, including former State Physician

of Ireland, on the pamphlet’s first page, Dickson experienced only indifference

and suspicion from Quebec officials. The lieutenant-governor of Quebec, Robert

Prescott commented, “It does not appear to me that this Country is yet Ripe for

such an Establishment.”[vi] Worse, the very qualifications Dickson

boasted about led Prescott and other paranoid British officials to conclude

that, “…from Circumstances that have taken place in Ireland…and from the

retired manner in which he lives compared with what might be expected of a man

in that station of Life—added to the Extraordinary Circumstances of a man in

such eligible Situation in his own Country to seek his Fortune among strangers,

I am induced to suspect that he may be actuated from motives different from any

that he may be expected to avow.”[vii]

Dickson’s position in Quebec was made more precarious

by the Quebec Attorney-General William Osgoode’s belief that he was a United

Irish Leader, namely “Dr. Dickson, the noted Irish partisan of whom such

honorable mention is made in the Report of the Secret Committee of both Houses

in Ireland…[who] came here under every Circumstance of Suspicion.”[viii] Dickson unfortunately shared a surname with

Dr. William Steele Dickson, a Presbyterian minister and the adjutant-general of

the United Irish rebels in Co. Down.

Even Dickson’s poem, a fulsome encomium to Robert and Lady Prescott and

an endorsement of British scientific and military achievements, could not allay

Quebec officials’ existing fears of Irish collusion with French and American

rebels in North America. Osgoode noted

cynically that “Doctor Dickson…in return for Three Dinners a week at the

chateau…wrote a poem called The Union of Science and Taste [sic] and talked of

Prescott’s reflecting ‘Lustre on the Throne.’

He took care to be off Scampato! alla fuga! before any intelligence

respecting him could be received from home.” Osgoode added that Upper Canada lieutenant-governor

Peter Hunter “regretted he had not stayed a little longer.” [ix] It was well that he hadn’t, since General

Hunter’s previous posting had been in Ireland, where he had been known for

impaling the heads of executed United Irishmen on gates.[x] Consequently, Dickson spent a fruitless six

months in Quebec under government surveillance.

|

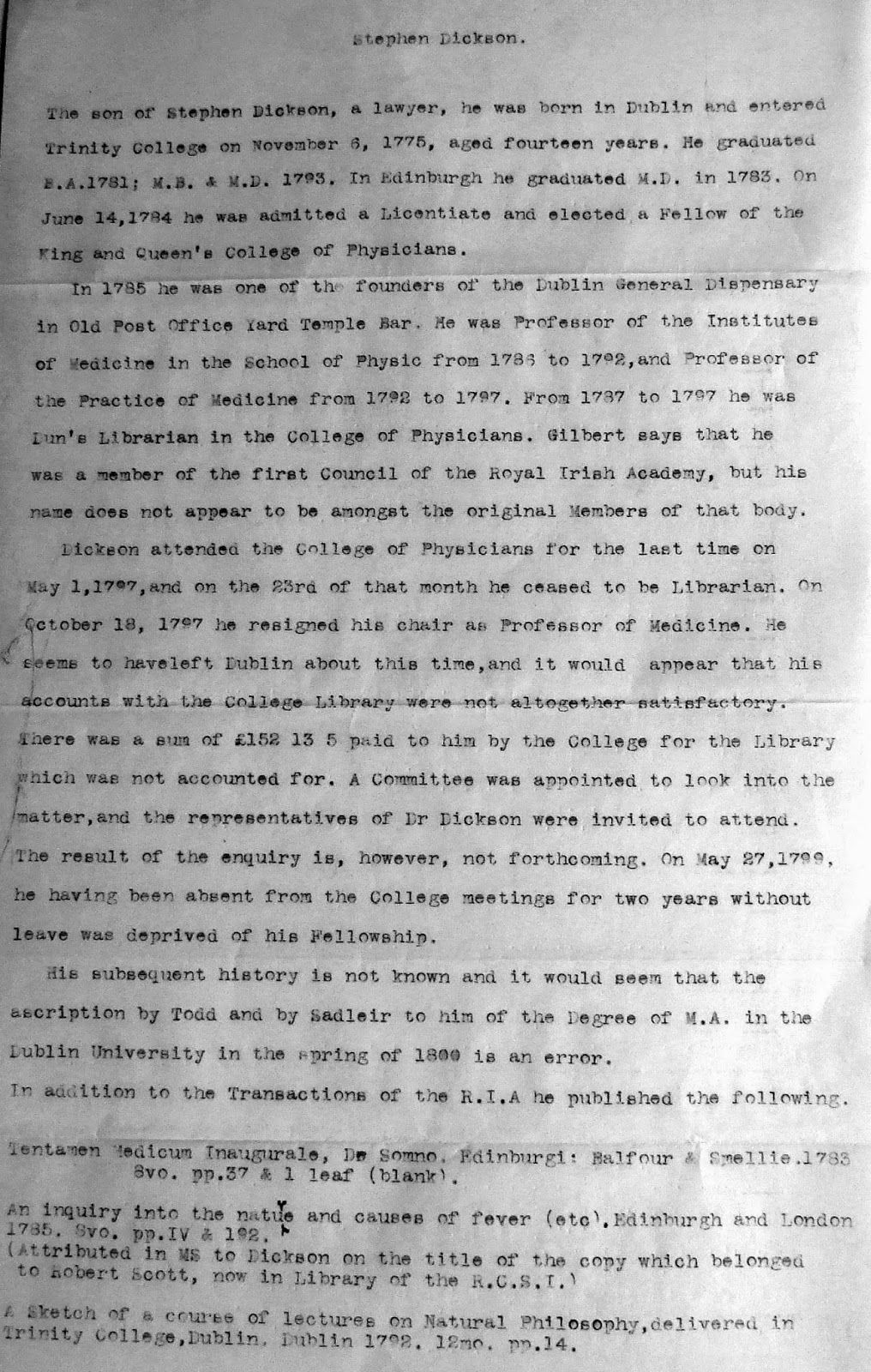

| Typescript note on the life of Dr Dickson (Kirkpatrick Index, RCPI) |

Before

departing for the United States, Dickson may have sold off many of his personal

effects, including his books, as suggested by a telling and rather poignant

document: a “Catalogue of Mr. Dickson’s Books,” described as “a large

collection of valuable books, the property of a gentleman gone to England.”[xi] (This catalogue may refer to another man

entirely, since Dickson never returned to the British Isles; however, in his

pamphlet Dickson had offered to donate his books to the Quebec college he

wished to found). These books may have

been Dickson’s own, since he actively subscribed to many significant

publications while in Dublin, or they may have been the missing books with which

Dickson is believed to have “absconded”.[xii] Unfortunately

no copies of this catalogue, which could have solved a major Irish

bibliographical mystery, appear to have survived.

Dickson

landed in South Carolina, and historical memoirs recall lectures in Chemistry

given at the Charleston library “by Dr. Dickson, an Irish gentleman, who was

said to be very accomplished.”[xiii] With a gift for incredibly bad timing,

however, Dickson arrived in Charleston at the onset of a yellow fever

epidemic. By the end of September 1799,

the South Carolina City Gazette had reported the deaths of “Dr. Stephen

Dickson, Fellow of the College of Physicians of Ireland, formerly State

Physician of Ireland,” his ten-year-old son, also named Stephen, and his wife.[xiv]

|

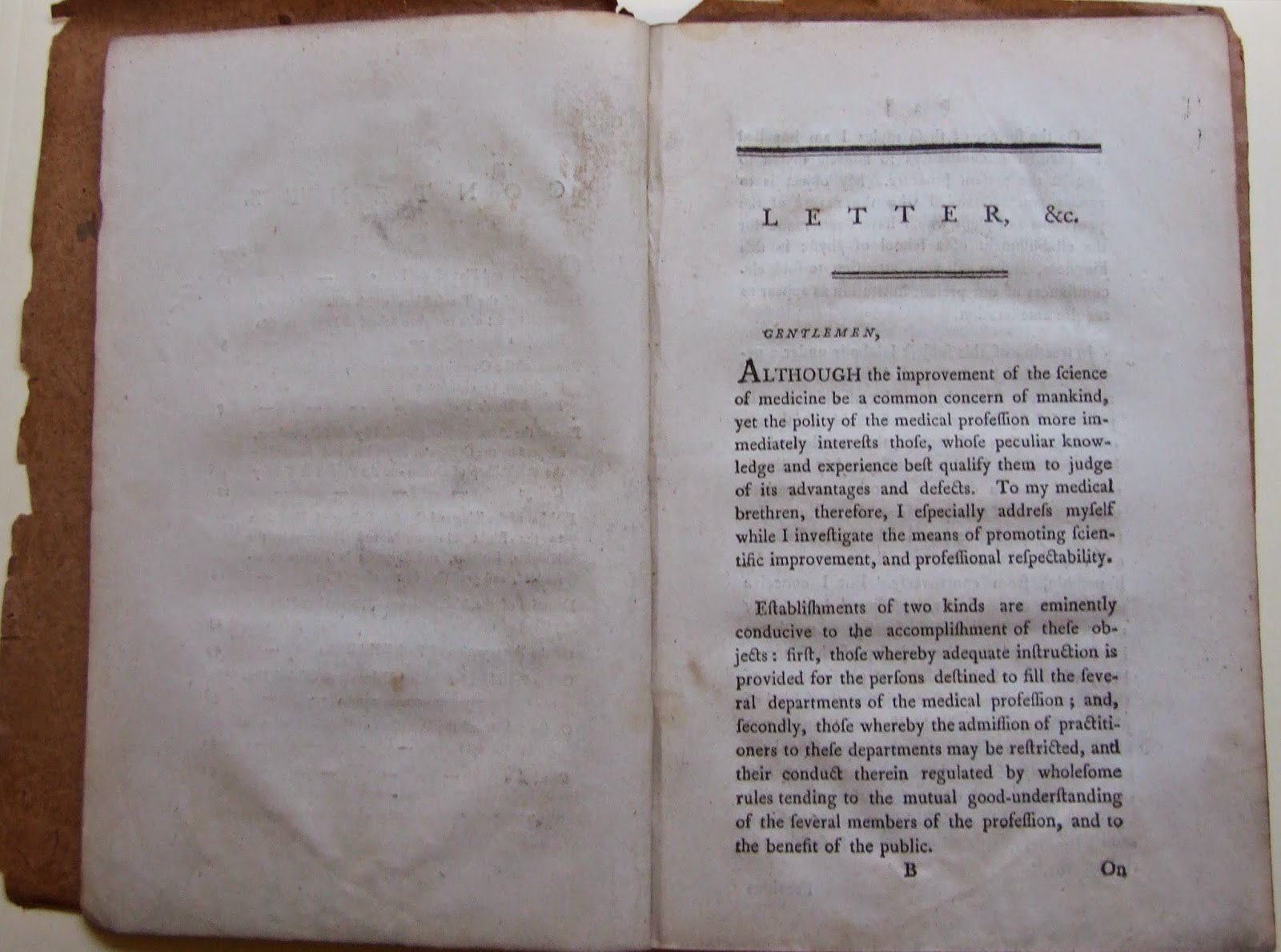

First page of A Letter from Doctor Dickson to his Medical Brethren Relative to the

School of Physic in this Kingdom (Dublin, 1795), which was published two years

before Dr Dickson's departure from RCPI and Ireland (RCPI Library, KP1834)

|

Dickson should not be remembered only for his professional incompetence and spectacularly bad luck. His Canadian legacy includes two publications dedicated to cultivating learning, especially "Taste and Science" in a new country, values consistent with his lifelong participation in educational and cultural societies, including the Royal Irish Academy, of which he was a founding member. His obituary holds the kindest and fairest last words on Dr Stephen Dickson: characteristically, he had "been arrested by the fatal messenger while engaged in pursuits calculated to infuse the highest kind of knowledge in the rising generation, in accomplishing which the force of his superior genius and attainments, softened by ease and affability were such as gained him the esteem of all who knew him...In a word, a man of science is snatched from Carolina".[xv]

|

(i) Robert W. Mills, “Dun’s

Library: the Library of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland.” Journal of the Irish Colleges of Physicians

and Surgeons, 24.2 (April 1995), p. 127.

(ii) Thomas Percy Claude

Kirkpatrick, History of the Medical

Teaching in Trinity College Dublin and of the School of Physic in Ireland. (Dublin, 1912), p. 229

(iii) Ibid. , p. 162.

(iv) Marie

Tremaine, A

Bibliography of Canadian Imprints 1751-1800 (Toronto, 1999), p. 552

(v) Stephen Dickson, Considerations on the Establishment of a

College in Quebec For the Instruction of Youth in Literature and Philosophy

(Quebec, 1799), pp. 13-14

(vi) Marie Tremaine, p.551

(vii) Ibid.

(viii) Ibid.

(ix) Ibid.

(x) Taylor, Alan. The

Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels and Indian

Allies. (New York, 2010), p.88

(xi) Tremaine, p. 550

(xii) Elizabeth Lake,

“Medicine.” The Irish Book in English 1800-1891. Vol. 4 of The Oxford History of the Irish Book. Ed. Murphy, James H. (Oxford, 2011), n. 11, p.

577

(xiii) Charles Fraser, Reminiscences of Charleston, Lately

Published in the Charleston Courier, and Now Revised and Enlarged by the Author

(Charleston, 1854),

p. 67

(xiv) Jeannie Heyward

Register, “Marriage and Death Notices from the City Gazette.” The South Carolina Historical and

Genealogical Magazine, 25.4 (Oct.

1924), pp. 188-189; “Marriage and Death Notices from the City Gazette

(Continued), 26.1 (Jan. 1925), p. 45

(xv) "Marriage and Death

Notices from the City Gazette.” The South

Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine.

25.4 (Oct. 1924), pp. 188