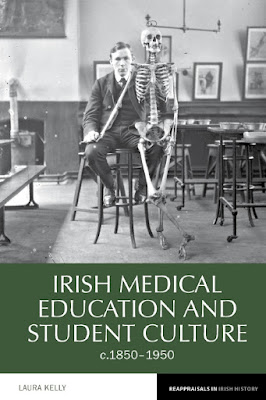

New Book: Irish Medical Education and Student Culture, c.1850-1950

Later this month we will be hosting the launch of Dr Laura Kelly's new book Irish Medical Education and Student Culture, c.1850-1950. To mark the launch of the book the publishers, Liverpool University Press, have shared the following interview with Laura about her research.

What drew you to this period, and why do you think this is the first comprehensive history of medical student culture on this period?

What drew you to this period, and why do you think this is the first comprehensive history of medical student culture on this period?

I’ve been really interested in the history of medical student experience ever since my masters thesis which focused on the social backgrounds and careers of Irish students who studied at the University of Glasgow in the nineteenth century. While studying for my masters I came across a book by Wendy Alexander on the history of the first female medical graduates at the University of Glasgow and then became interested in exploring the first generation of Irish medical women’s experiences, which was the topic of my PhD and subsequent first book. I’ve also been inspired and influenced by historians such as John Harley Warner, Keir Waddington, Jonathan Reinarz, Marguerite Dupree and Anne Crowther, who have written fascinating and important studies of medical education and student culture in the United States and Britain, as well as the work of Greta Jones, who has published widely on the history of the Irish medical profession. I became interested in discovering what was distinctive about the Irish medical student’s experience and in understanding how medical education evolved in Ireland over the nineteenth and twentieth century, as well as wanting to understand commonalities between the Irish case study and studies of medical education internationally.

The period 1850 to 1950 is a really fascinating one, not just in terms of the significant political and social changes taking place in Ireland, but also more broadly with regard to the increasing professionalization of doctors in this period, and attempts at reform of education. Class and social mobility are important concerns of the book.

I was surprised to find that there had been no comprehensive study of the history of Irish medical education since Charles Cameron’s survey of the Royal College of Surgeons and other Irish medical schools, published in 1886. Since then, there has been little written on the history of medical education in Ireland, with the exception of important articles by Greta Jones who has examined themes such as the emigration of Irish medical graduates and the Rockefeller report on Irish medical education, and my own first book, which has one chapter on women medical students’ educational experiences. There have also been a number of institutional histories also, but these tend to focus on the staff and administration of medical schools, rather than looking at the experiences of the students who attended them. My book looks at all of the Irish medical schools, rather than focusing on one, and importantly, it places students at the centre of the analysis.

You used a variety of sources including novels, newspapers, student magazines, doctors’ memoirs, and oral history accounts. Did this sources reveal anything that surprised you or changed the direction of your research?

I found that student newspapers and magazines were remarkable in terms of getting a glimpse of what life was like for medical students in the past. Most Irish universities had their own student papers from the 1900s onwards, and these had news on the medical schools as well as information about students’ extra-curricular activities, and poems and short stories written by students themselves. They revealed a lot about what it was actually like to study medicine in the early twentieth century, as well as giving me as sense of representations of medical students and attitudes towards them. The records of university sports clubs and discussions of pranks in the student press also meant that I became more interested in the interplay between sport, medical student culture and masculinity.

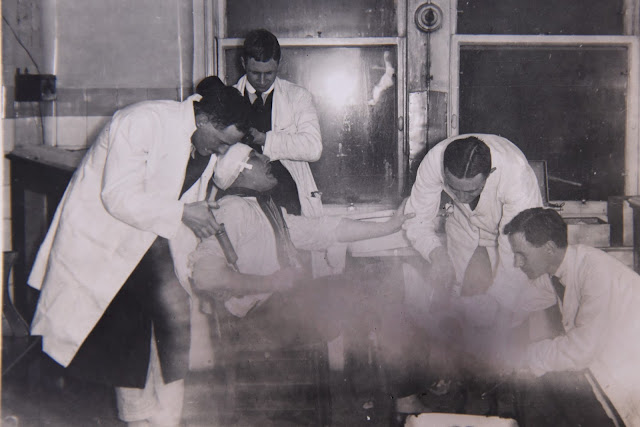

|

| Trinity Medical Students, c.1920s |

Diaries were also an important source for me, such as the diary of Alexander Porter, who studied medicine in Dublin in the 1860s. Porter had a challenging time as a student and frequently wrote about his fears about money and establishing himself in a medical career after graduation. These personal perspectives are invaluable.

There are also numerous memoirs written by Irish doctors which were very interesting in terms of collective memory and the particular image that doctors tried to present of their student days. In terms of novels, perhaps the most famous fictional Irish medical student is Buck Mulligan, who features in James Joyce’s Ulysses. He was based on Irish doctor Oliver St. John Gogarty, who published his own memoirs and a novel about medical student life called Tumbling in the Hay. A lesser known novel I looked at was G. M. Irvine’s The Lion’s Whelp (published in 1910) which is a fictional account of the experiences of a medical student at Queen’s University in Belfast.

My favourite part of the research, however, involved conducting oral history interviews with 24 men and women who had studied at Irish medical schools in the 1940s and 1950s. It was really enjoyable to hear about their experiences and to get those personal insights into the challenges they faced in studying medicine, as well as learning about the quality of teaching, and the gender dynamics. All of these personal perspectives really brought the book to life.

How did the medical student experience change in Ireland between 1850-1950?

For the nineteenth century, and much of the twentieth century, the British and Irish medical profession were inextricably linked and had much in common. In common with their counterparts in Britain, elsewhere in Europe, and the United States, Irish medical students were warned about the importance of cultivating diligence, good behaviour and avoiding the company of idle students in an effort to improve the behaviour of medical students, who were conventionally viewed as badly-behaved, an image which persisted into the twentieth century. As reports of bad behaviour by medical students began to decline, their image was remoulded into a more respectable one by the late-nineteenth century. Additionally, traits such as nobility and heroism became more important, thus reinforcing ideals about medicine being a ‘manly’ profession, particularly significant as women began to be part of the student body in Ireland from the 1880s. Sport, in particular, rugby, became important in maintaining cohesive social bonds.

|

| Sir Patrick Dun's Hospital Rugby Team |

I was interested to discover that teaching at Irish medical schools was generally of a poor standard for much of the nineteenth and twentieth century in Ireland. On top of this, Irish medical schools were beset with economic difficulties which meant that practices such as night classes, grinding and the issue of sham certificates were common in the earlier period. Moreover, owing to increased competition between medical schools, Irish students had a huge amount of power as consumers in the period. Medical students were not passive consumers either. Students also actively began to get involved in the concerns of the profession in the nineteenth century too and their complaints highlight not only the inadequacies of teaching at Irish schools, but also that students were beginning to see themselves as part of the profession and therefore felt entitled to get involved in such discussions. For instance, student protests were often concerned with appointments to hospital or university staff which students not agree with, or cases where an “outsider” had been appointed. Emigration was also an important part of medical student life across the 100 year period.

You also start to see changes in terms of the student body from the 1940s and 1950s. There were more international students, as well as ex-servicemen who began their medical studies in Ireland. Also, following the 1936 change in canon law, medical missionary nuns gradually became part of the student body, in particular at the medical schools at UCD and UCC which had a strong Catholic ethos.

Medical students of the past also share much in common with their counterparts today. Emigration is still really common for new Irish medical graduates, while there are also concerns about medical students possessing the appropriate traits to become good doctors, which partly resulted in the introduction of the HPAT (Health Professions Admissions Test) in 2009. However, there have also been important changes. For instance, today female students predominate in medical school applications in Ireland, a pattern which is mirrored by medical schools internationally. And medical students also face new concerns such as ‘burn out’ and the working pressures experienced by junior doctors.

How did religious divisions affect institutions and the student experience?

There was significant sectarianism within the Irish medical profession in both the nineteenth and twentieth century, however, I was surprised to find that this does not appear to have affected Irish students’ experiences in a major way. Oral history respondents who studied in the 1940s and 1950s also did not recall major rivalries between the different institutions; often such rivalries were quite benign in nature, and were played out on the sporting field. Religion was also an important factor in choice of medical school, and evidently, although Catholics began to increase in numbers in the medical profession from the mid-nineteenth century, they still continued to attend the Catholic University and the Queen’s Colleges over Trinity College, and for later generations of Catholic students in the mid-twentieth century, University College Dublin and the former Queen’s Colleges were preferred.

|

| Trinity Medical Students, c.1920s |

What was the role of women in Irish Medicine at this time?

Many people don’t know that Irish medical schools were at the forefront with regard to the admission of women to the medical profession in the nineteenth century. The King and Queen’s College of Physicians in Ireland was the first institution in the United Kingdom to take advantage of the Enabling Act of 1876 and admit women to its degrees in 1877. From the 1880s, Irish medical schools opened their doors to women students. Numbers of female students matriculating at Irish medical schools were initially low. In the ten year period between 1885 and 1895, only forty-one women matriculated at Irish medical schools. Numbers of female medical students gradually increased during the years of the early twentieth century, peaking as they did in Britain during World War One, before declining again after the war. At Queen’s College Belfast, for example, one in twenty medical students in 1912 were female, while by 1918 one in four were female.

Women medical students, being in the minority, stood out in the medical student body and were often characterised in a certain way. In Ireland, female medical students were often thought to have a ‘civilising’ effect on the male student body. At the same time, female medical students were often figures of fun in the contemporary student press. In the student press, the male medical student was usually depicted as boisterous, sporty, and extremely sociable. Women medical students, on the other hand, were generally represented as being better behaved, more studious and hard-working than their male counterparts.

Although my earlier research has shown that the first generation of women students at Irish universities were treated in a positive manner, moving into the twentieth century and a more conservative Irish society after the establishment of the Irish Free State, women medical students became an increasingly segregated part of the student body.

How does this book pave the way for further research in the development of medical education throughout Irish history?

I hope it will! I feel that there is much potential for future research on the history of university education and student culture more broadly in Ireland. Although there have been a number of histories of Irish universities, as with histories of medical schools, these have tended to focus on administrative changes in these institutions and on the professors involved in teaching. There is much scope for research into the experiences of students and student culture more generally in Ireland, and as this book shows, there are a variety of sources available to do this. Moreover, I would love to know more about the experiences of medical students who trained in the 1960s and 1970s. There is also further scope for further work on the history of the Irish medical profession. In recent years, there have been a number of valuable studies which have significantly enriched our understanding of the Irish medical profession, for instance, with regard to issues such as emigration (Greta Jones), the First and Second World War (David Durnin), in the field of psychiatry (Catherine Cox) and in the medical missionary movement (Ailish Veale). Considering the huge amount of emigration of Irish doctors in the 1940s and 1950s, a project which explored the experiences of doctors who emigrated in this period would also enrich our understanding of the Irish medical profession.

The launch of Irish Medical Education and Student Culture, c.1850-1950 will take place at 6.30 on Wednesday 22nd November in RCPI, No. 6 Kildare Street. The book will be launched by our new President, Prof Mary Horgan.