Sir Robert John Kane, Irish chemist

|

Portrait of Robert John Kane, dated 1849

(RCPI Archive: VM/1/2/k/1) |

Robert John Kane was one of the most famous Irish chemists.

Born in Dublin in 1809, Robert John

Kane was the son of John Kean, a former United Irishman who had participated in

the 1798 Rebellion. John Kean fled to Paris following the failure of the

Rebellion, where he studied chemistry. In the early 1800s Kean changed his name

to Kane, returned to Dublin, and set up a business as a lime-burner. From a

very young age, his son Robert John Kane showed a great interest in chemistry,

stimulated by the activities of his father’s factories. Something of a child

prodigy, Kane published his first scholarly paper in 1828 before his had

reached the age of 20. In 1829, Kane became a Licentiate of Apothecaries’ Hall,

entered Trinity College Dublin, and made an important scientific contribution

when he described the natural arsenide of manganese, which was named Kaneite in

his honour. Two years later, in 1831, he was appointed Chair of Chemistry in the

Apothecaries’ Company, where he was known as ‘The Boy Professor’. In the same

year, he founded the Dublin Journal of Medical and Chemical Science (now

the Irish Journal of Medical Science), and published his first book, Elements of Practical Pharmacy.

|

| Introduction to Elements of Chemistry |

This relentless activity

left little time for Kane’s medical studies. In 1828 and 1829 he acted as a

clinical clerk to Dr William

Stokes in the Meath Hospital, and eventually graduated from Trinity with a

BA in 1834. He became a Licentiate of College of Physicians in Ireland in 1835,

before proceeding to the Fellowship of the College in 1843. Kane never

practiced as a doctor, however, as he concentrated more and more on pure chemistry.

He lectured in Natural Philosophy at the Royal Dublin Society between 1834 and

1846, and in this period made his greatest achievements in chemical research

which earned him an international reputation. Breakthroughs included the

isolation of acetone from wood spirit and pioneering research on

the combination of ammonia with metallic salts. Kane’s last important effort in

pure chemistry was his book Elements of Chemistry,

which was published in three volumes in 1841 and 1842. The book was a

bestseller which included the most recent discoveries and applications of the

science to medicine, chemistry and the arts, and contained much of what would

now be classed as physics.

In the early

1840s, Kane abandoned chemistry to focus on the promotion of industry and

industrial knowledge in Ireland, which culminated in the publication of his Industrial Resources of Ireland in 1844.

In 1846 he was knighted, and became the first President of Queen’s College,

Cork, a position he held until 1873. A long-time associate of the Royal Irish

Academy, Kane acted as its President between 1877 and 1882. In his later years,

Kane was a strong advocate for non-denominational education in Ireland. He died

in 1890.

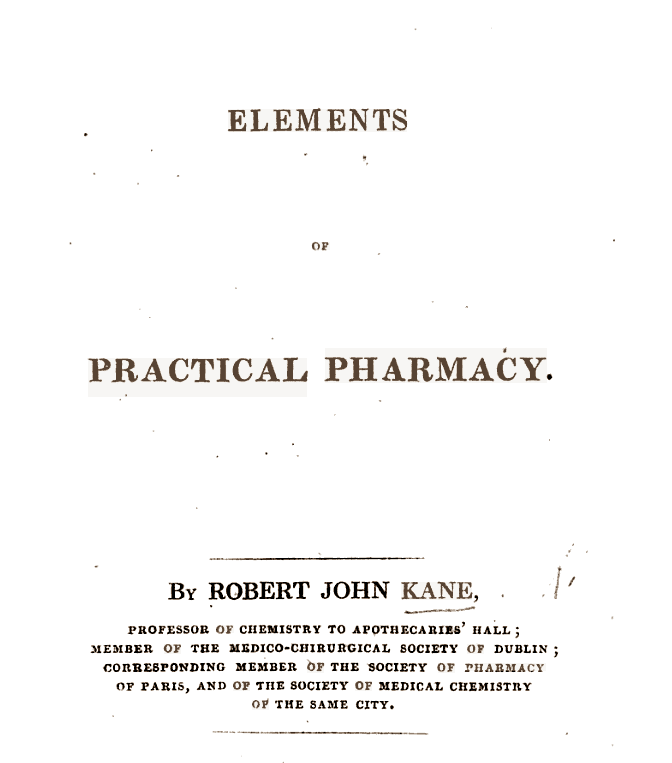

In addition to Elements of Chemistry,

there are many items relating to Robert Kane in the library and archival

collections of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland. These include his Elements of Practical

Pharmacy (1831). Intended ‘to fill up that space which exists between the mere

detail of the processes in a Pharmacopoeia and the theoretic explanations of

their nature’, Kane (22 years old at the time) was elected to the Royal Irish

Academy on the strength of this first book.

|

| Title page of Elements of Practical Pharmacy |

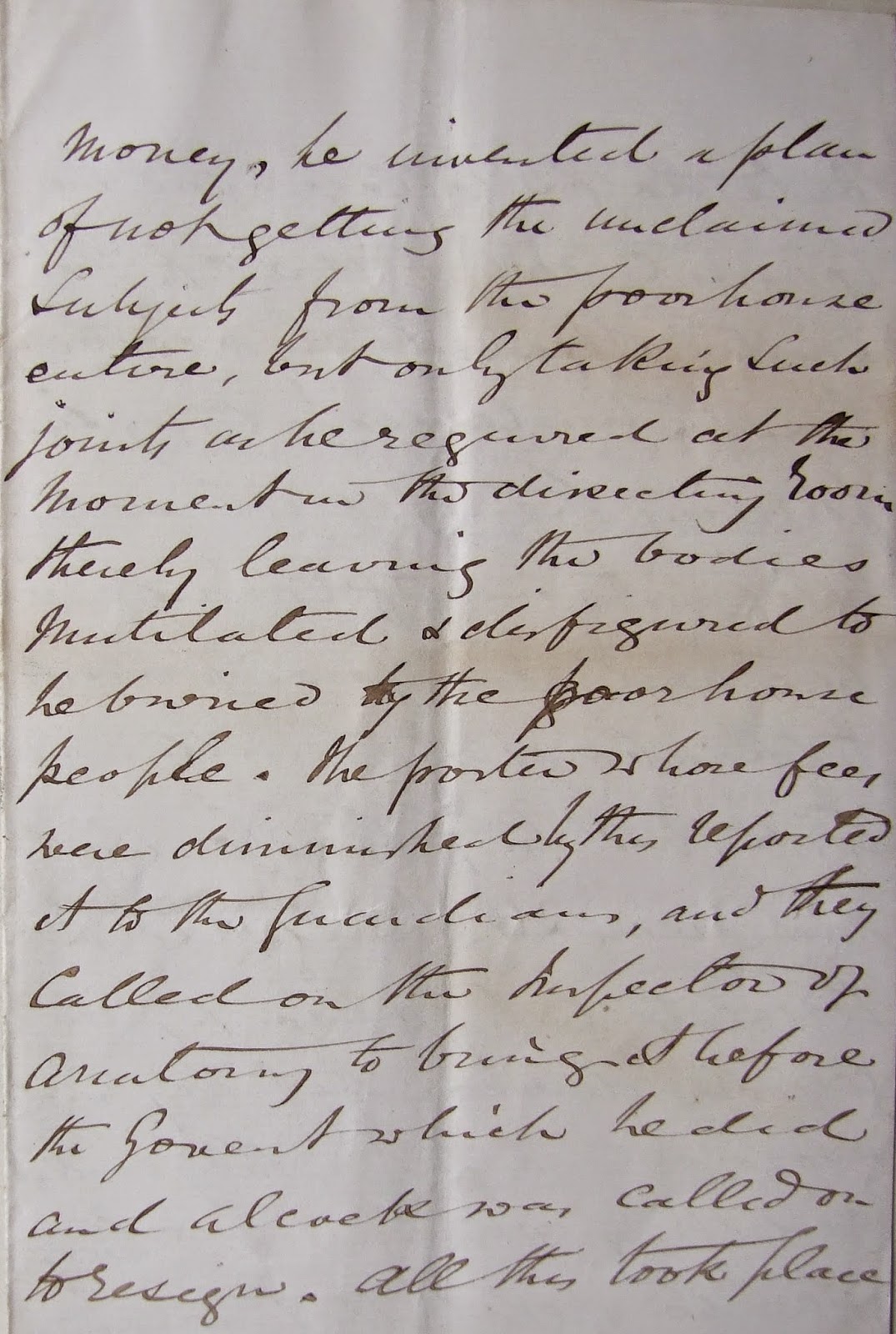

There are also items in

the RCPI collections which relate to Kane’s later life. One such item is a

letter of 25 May 1873 from Robert Kane to Dominic Corrigan, President of the

College of Physicians from 1859 to 1863, and a fellow supporter of

non-denominational education. In this letter, Kane informed Corrigan of the activities

of Benjamin Alcock, a colleague of Kane’s in Queen’s College, Cork, between

1849 and 1855. Alcock was a Professor of Anatomy in Queen’s College, and in

order to teach his students he needed dead bodies for the dissecting room. Kane

objected strongly to Alcock’s methods of obtaining bodies. He described how Alcock

had invented a plan ‘of not getting the unclaimed subjects from the poor house

entire, but only taking such joints as he required at the moment in the

dissecting room, thereby leaving the bodies mutilated and disfigured to be

buried by the poor house people’. After a porter working in the poor house

reported these shocking acts, Alcock was forced to resign. Did Kane know of Corrigan’s own grave

robbing exploits during his student days? No reference is made to

this in the letter, and unfortunately, there is no surviving letter of reply

from Corrigan.

|

| Page of Robert John Kane's letter to Dominic Corrigan. RCPI Archive (DC/5/14). |

Fergus Brady,

Project Archivist