'The numbers flocking into Dublin bring much contagion of a most dangerous character with them': Cork Street Fever Hospital and the Great Famine

Successive

failures of the potato crop led to more 1 million deaths in Ireland between

1845 and 1849. The majority of these

deaths have been attributed to infectious diseases. In Dublin, an influx of

refugees from the countryside during these years resulted in increased

vagrancy, overcrowding and neglect of personal and domestic hygiene, creating

optimum conditions for the spread of fever.

|

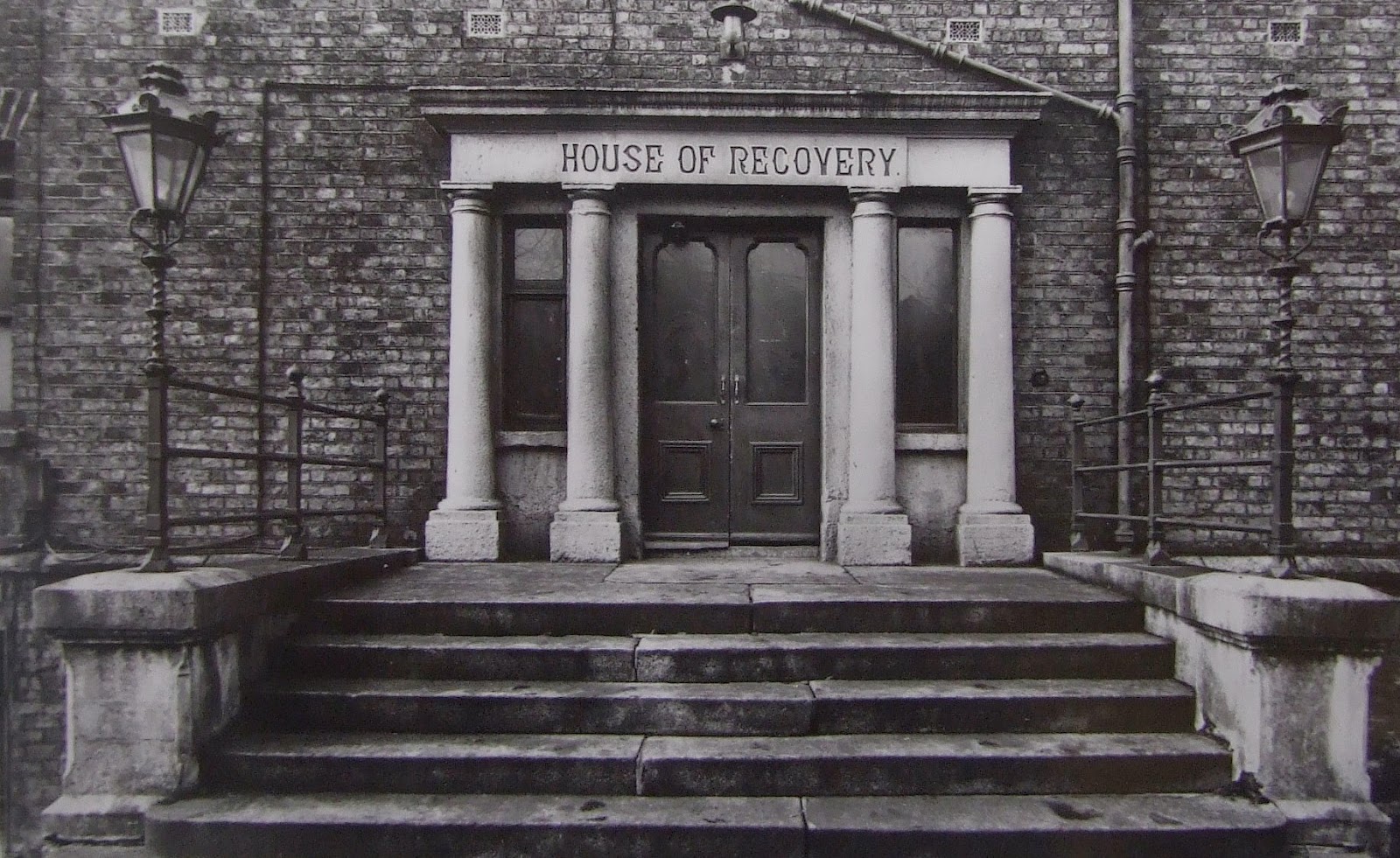

| Picture of one of the wards in Cork Street Fever Hospital reprinted in a number of annual reports (CSFH/1/2/1) |

Admissions and Accommodation

In the late

1840s hospitals in Dublin came under severe pressure to cope with soaring

demands for admissions, particularly during epidemics of typhus in 1847 and of

cholera in 1849. Cork Street Fever Hospital in the Dublin Liberties was one

such hospital. In early 1847 the deepening crisis began be reflected in minutes

of meetings of its Managing Committee. On 27 May 1847 it was noted that:

‘As

it appears that several Patients are lying on the floor:

Ordered that fifty stretchers be forthwith provided, twenty-five

of three feet wide, twenty-five of two feet six inches’.

The need to

accommodate more patients exercised the Managing Committee greatly during these

years. In May 1847, James W. Cusack and David C. Latouche, members of the

Managing Committee, sent a letter to Thomas N. Redington, Dublin Castle, in

which they expressed their fear that:

‘The numbers that are every day flocking into Dublin to embark for

America bring much contagion of a most dangerous character with them, and we

have every reason to apprehend the most serious consequences to the health of

the town’.

|

| Original Entrance to Cork Street Fever Hospital (CSFH/7/1/6) |

Cusack and

Latouche asked for funds to enable the erection of temporary huts to meet increasing

need to admit more patients, a request that received sanction from the Lord

Lieutenant. In late 1847 a number of tents and four wooden sheds providing

accommodation for an extra 480 patients were erected on the Cork Street

grounds.

The table

below shows that even this extra accommodation did not meet demand as the

situation worsened in late 1847, and applications for admission consistently

outstripped available space in the hospital.

Month

|

Applications for Admission

|

Admissions

|

Rejected Applications for Admissions

|

October

1845

|

330

|

254

|

76

|

November

1845

|

302

|

229

|

73

|

December

1845

|

345

|

256

|

89

|

January

1846

|

458

|

303

|

155

|

February

1846

|

379

|

275

|

104

|

March

1846

|

358

|

285

|

73

|

April

1846

|

416

|

310

|

106

|

May 1846

|

446

|

294

|

152

|

June

1846

|

368

|

251

|

117

|

July

1846

|

370

|

292

|

78

|

August

1846

|

355

|

262

|

93

|

September

1846

|

432

|

341

|

91

|

October

1846

|

560

|

380

|

180

|

November

1846

|

510

|

359

|

151

|

December

1846

|

625

|

393

|

232

|

January

1847

|

656

|

411

|

245

|

February

1847

|

744

|

558

|

186

|

March

1847

|

943

|

704

|

239

|

April

1847

|

1105

|

670

|

435

|

May 1847

|

1419

|

703

|

716

|

June

1847

|

1939

|

951

|

988

|

July

1847

|

1492

|

790

|

702

|

August

1847

|

555

|

405

|

150

|

September

1847

|

1365

|

656

|

709

|

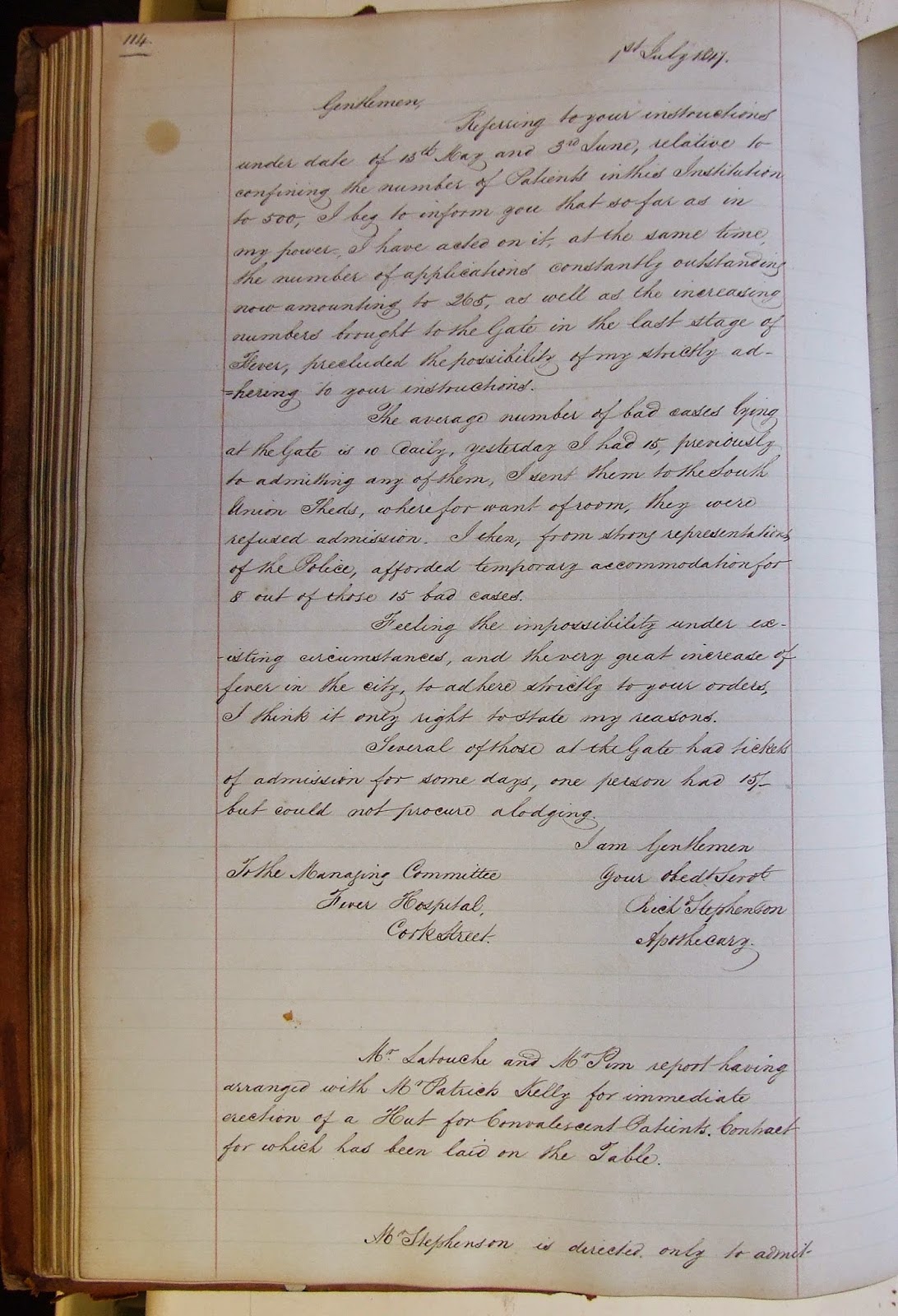

The

distress faced by those rejected at the hospital gates was reflected in a

letter from the hospital Apothecary, Richard Stephenson, to the Managing

Committee on 1 July 1847. Stephenson stated that:

‘The average number of bad cases lying at the Gate is 10 daily.

Yesterday I had 15. Previously to admitting any of them, I sent them to South

Dublin Union Sheds, where for want of room, they were refused admission. I

then, from strong representations of the Police, afforded temporary accommodation

for 8 out of 15 of those cases’.[3]

|

Letter of 1 July 1847 from Richard Stephenson to the

Managing Committee, reproduced in a minute book

(CSFH/1/1/9)

|

The Managing

Committee responded blankly by stating:

‘Mr. Stephenson is directed only to admit a number equal to one

half the number of persons discharged until the number of patients in the

Hospital shall be reduced to 500’.

Financial Pressure

Although

the response of the Managing Committee to Stephenson seems callous by today’s

standards, it was the product of severe overstretching of resources. As a

voluntary hospital, Cork Street depended on subscriptions from philanthropists

and Government grants to sustain its operations. As early as March 1847, the

Managing Committee were expressing fears to the Lord Lieutenant in Dublin

Castle that:

‘...the pressure on the Hospital has become so great within the

last two months and appears to be so rapidly increasing, that we fear even that

Estimate will be very much below the actual Expenditure’.

Additional

financial aid from Dublin Castle was not forthcoming, however. A letter from

Thomas N Redington, Dublin Castle, to James Montgomery, Register of Cork Street

Fever Hospital, informed him that:

‘the Grant for the Cork Street Fever Hospital will be proposed for

£3,800, being the same amount as for several years previous to 1843’.

The

gravity of the developing crisis does not appear to have been recognised by

Dublin Castle at this stage, as Redington’s letter continued by stating that:

‘the Lordships do not consider it advisable to increase the vote

to be proposed in aid of the funds of the Hospital to meet the expenditure

arising from a temporary pressure of this nature’.

|

| Famine memorial in Dublin City Centre |

In fact as

the Famine progressed Cork Street Fever Hospital, in common with all Dublin

medical charities, received cuts rather than increases to its funding. In 1848 a ten percent

reduction in funding was imposed, and in 1850 the Government announced its

intention of completely withdrawing the grant from all Dublin medical

charities, a proposal which caused a great deal of outrage at meetings of the

Cork Street Managing Committee.

Government policy of gradually reducing the grant was only abandoned in 1851,

by which time the most virulent period of the Famine had passed.

Fergus Brady,

Project Archivist