Women in Medicine II: Sophia Jex-Blake and the London School of Medicine for Women

|

| Dr Sophia Jex-Blake |

Sophia Jex-Blake was one of the most vocal, and best known, advocates for the medical education of women. The daughter of a lawyer, Jex-Blake had studied medicine in America and at Edinburgh University. However, as women were not able to receive degrees from British universities she could not qualify and register as a medical practitioner. In 1874 Jex-Blake published 'The Medical Education of Women', a pamphlet expressing the case for the medical education of women. In the same year she helped to found the London School of Medicine for Women, the first medical school in the British Isles to train women.

The London School of Medicine for Women was founded in 1874 by a group of medical practitioners and campaigners for women's rights. The aim was to provide a school where women, excluded from the teaching hospitals and universities could study medicine. Financed entirely by private subscription the school opened on 12 October 1874 on Henrietta Street in London. In its first year it had 23 students.

|

| The London School of Medicine for Women |

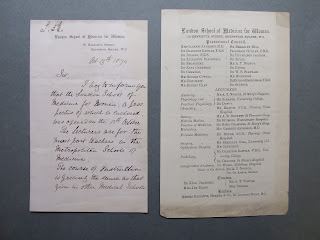

The London School of Medicine for Women faced two major drawbacks. Firstly, none of the 19 medical examining bodies in the British Isles would grant the school's request for official recognition of its courses. The importance of this official recognition can be seen in one of the very first acts of the School, which was to write to all the examining bodies on this point. The letter to the King and Queen's College of Physicians in Ireland was written on 13th October 1874, the day after the School opened. There is no record in the archive of the College of Physicians' response but it must have been negative as they were to receive another letter on the same subject four years later. The second difficulty facing the school was the problem of persuading any hospital to allow the female students to train on their wards. Eventually the Royal Free Hospital decided to allow female to train on their wards.

|

| RCPI/2/3/3/5 - Letter from the London School of Medicine for Women |

However, the major breakthrough for women wanting to study medicine came in 1876 with the Enabling Act, which allowed the 19 medical examining bodes to decide if they wanted to accept female applicants. The response to the Enabling Act, especially by the King and Queen's College of Physicians in Ireland, will be the focus of the next post in this series.