Women in Medicine III: ‘The Turning Point in the Whole Struggle’

This is the third and final post in this series looking at the admittance of women to the medical profession in the late nineteenth century. Click here for the first and second posts. The posts are all based on the exhibitions looking at diversity in Irish Medicine which were created for this year's Heritage Week Open Day.

In 1876 the British government gave in to the mounting pressure to allow women to qualify as doctors, and passed the

Enabling Act. This act allowed the medical licensing bodes to allow candidates holding degrees from foreign universities to sit their examinations. As women could study medicine at some foreign universities this opened the way for women to enter the medical profession in Britain.

|

| Dr Aquilla Smith |

In October 1876 the London School of Medicine wrote to the King and Queen's College of Physicians of Ireland again asking them to recognise their course. The College took this request much more seriously than they had two years earlier. They established a committee to consider the request, and send

Dr Aquilla Smith to visit the school. Smith wrote a very positive report on the school, its teaching and facilities, he recommended that the College should recognise their courses.

The following January the College's examinations committee decided to issue their licentiate in medicine to Miss Eliza Dunbar, despite a last minute attempt to block the decision. By doing so the College became the first institution in the UK to allow a woman to qualify in medicine. Four months later, Sophia Jex-Blake receive her licentiate from the College, Jex-Blake describes the King and Queen's College of Physicians of Ireland's decision as 'the turning point in the whole struggle'.

In a recent thesis on the subject,

Dr Laura Kelly has identified four key reasons why the College took such a liberal attitude, and became the first to admit women. Firstly, she identifies a liberality towards the education of women in Ireland. Secondly, there were financial incentives. The College was short of money and fees were a crucial source of income, admitting women offered a new income stream. Thirdly, admitting women offered no direct threat to their own member's medical practices, as most of the women applying had no intention of practicing in Ireland.

|

| Dr Samuel Gordon |

Finally, the personalities on the College's council at the time were important in pushing this decision through. Important council members were Dr Aquilla Smith, who showed himself to be very favourable to the London School of Medicine for Women.

Rev. Dr. Haughton, both a protestant divine and a doctor, had long supported the access of women to medicine; in 1874 he had proposed admitting Louisa Atkins to the College. His religious views may have influenced his position, as he seems to have viewed medicine as a vocation not a profession, and so would not have wanted to prevent women following their 'call'. Finally, the President at the time was Dr Samuel Gordon, described as 'paternal and kindly in manner', he also had 9 daughters!

|

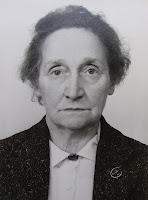

| Dr Mary Hearne |

In the decades following other medical licensing bodies followed the College's lead, with Trinity finally admitting women in 1904. The number of women applying to the College fell steadily as other opportunities opened to them, partly as the College's License was not valued as highly as a university degree. In 1915 the College changed its by-laws to allow women to become Fellows; Mary Ellice Thorne Hearne was the first female to be elected Fellow in 1924.

If you are interested in finding out more about this topic Dr Laura Kelly's thesis is

available here.